No Such Thing As a Summative Assessment

Educators differentiate between two different types of assessment–formative and summative. Formative assessments are meant to drive instruction and help teachers differentiate for their students. Summative assessments, on the other hand, are meant to show the cumulative knowledge which a student has acquired over the course of a unit of study. Summative assessments, in their traditional form, are used to assign grades or marks, and are usually the last thing students do before moving on to the next unit of study. But what if there was no such thing as a summative assessment?

‘What if there was no such thing as a summative assessment?‘

I want to stress two different aspects of this statement. Firstly: There is no such thing as a summative assessment. What I mean by this is that assessment of student understanding can (and should) take multiple forms. The typical paper-based summative assessment is already being challenged, and rightly so. This is a format that many students have difficulty with. If you were to sit down and talk with one of these students they would likely be able to tell you all sorts of things about the topic at hand–geometry, states of matter, character motivations–however, they freeze up the moment you place the assessment in front of them. This is because paper based tests often involve a series of instructions, and require some writing. In this case, what’s really being assessed is the students’ ability to read and write, and if you are assessing a unit of inquiry, or a social studies or science unit, you could be missing a large chunk of what that student actually understands. You are probably already thinking of a few students in your classroom because when you get their assessment back you think to yourself ‘I know she could have done better’. In fact, when it comes to reporting time you might just bump that student’s grade up because you instinctively know that she was capable of more. However, the same thing might occur with another student when it comes to a summative project, a presentation, or a portfolio. I’m not going to give you the whole spiel about learning modalities, but suffice it to say that current research has proven that students do not learn in different ways (see this article for a discussion of learning modalities.). However, students are capable of SHOWING their learning in different ways and to different degrees. To get the most accurate view of a student’s understanding of a unit, we need to offer them ‘multiple opportunities for success’.

‘To get the most accurate view of a student’s understanding of a unit, we need to offer them multiple opportunities for success.’

When I design, or choose, summative assessment measures, I base my choices on three important aspects:

- Time

- Modality/Subject

- Independence/Collaboration

TIme is taken into consideration for the simple fact that it is limited. I want to give my students multiple opportunities for success, but I can’t fit in four lengthy and involved summative assessments. Therefore, I need to make sure that a couple of the assessments are quick and easy. These could take the form of an exit slip, or an interview.

I use the term ‘modality’ to describe the way in which students show their understanding. These are not the supposed learning modalities that we are all familiar with (kinesthetic, visual, auditory, tactile), but different approaches that the student takes in presenting their knowledge. This is important to consider for the reasons already stated–some students may be more capable of explaining their understanding in writing, while others may find more success in building a model or giving a presentation.

The level of independence or collaboration is considered because we need to ascertain whether students are capable of demonstrating understanding in both contexts. Some students work well in a group, and are able to synthesize their understandings with those of their peers. Other students do their best work when they have the chance to extend their thinking on an individual basis.

Finally, the final assessments should cover all lines of inquiry or outcomes. Not every measure needs to cover all the outcomes, but each outcome should be addressed in some way, through at least one, or more, of the assessments. This is another reason I like to give multiple assessments; because it is nice to focus each assessment on a limited number of outcomes. This makes the assessments more clear for the students.

I have created the graphic below to show how these different elements merge to create diverse types of assessment experiences for students. The ideal situation would be to cover each subelement in some way through one of the assessment measures.

| Time | Modality/Subject | Independence/Collaboration | Outcomes |

| Time Intensive | Read/Write | Independent | Outcome 1 |

| Brief | Draw | Partners | Outcome 2 |

| Present | Small group | Outcome 3 | |

| Create | Outcome 4 | ||

| Explain (oral) |

As an example, let me share with you the summative assessments I gave my students for our grade 4 unit on energy. Now, I can’t take credit for all of these, as I just joined the grade 4 team this school year, and a couple of these assessments were already in place when I came on. The central idea for this unit is: Humans use their understanding of the different forms of energy to create and innovate. The lines of inquiry, or desired understandings are: 1) The forms of energy (kinetic and potential), 2) How energy is stored, transferred and conserved, as it relates to electricity, and 3) How we use our understanding of energy to create and/or design (the design cycle).

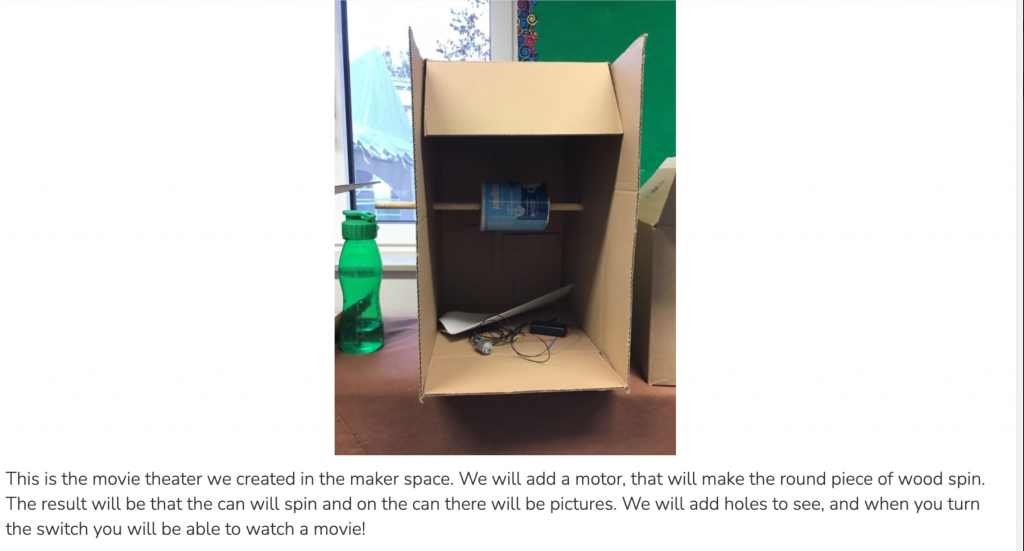

The first assessment was a collaborative energy project. Groups of students were given the task of building something which would demonstrate at least two different types of energy (some type of potential energy and some type of kinetic energy). Once the project was complete, they recorded themselves on Seesaw explaining the different types of energy, how the energy was transferred, and the challenges and successes the group experienced while working through the design cycle. This project was time intensive, involved drawing, creating, and presenting, was carried out by small groups, and covered all three outcomes.

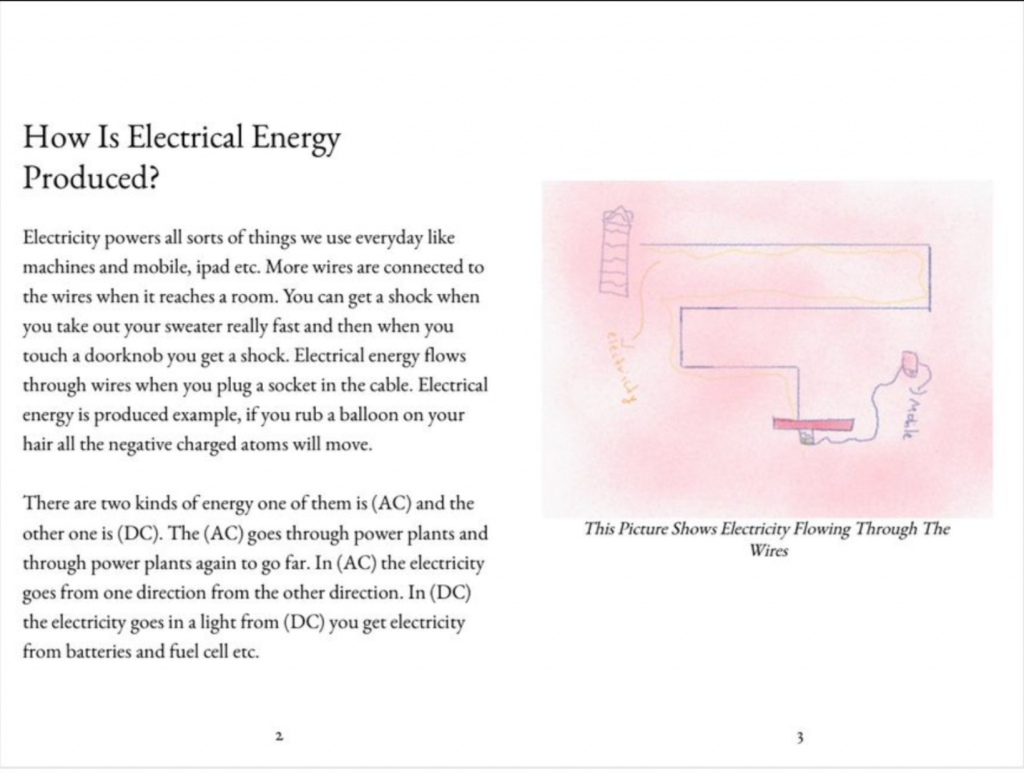

The second assessment was an energy book which was written and designed by groups of students. This project connected to our reading workshop unit on informational texts. Students read and took notes on an energy topic over a number of weeks. They then learned how to turn their notes into paragraphs. Finally, they worked with their group to synthesize their learning into a book, adding an introduction and conclusion, as well as text features. This assessment measure was time intensive, involved reading and writing, was carried out independently and in small groups, and covered outcomes 1 and 2.

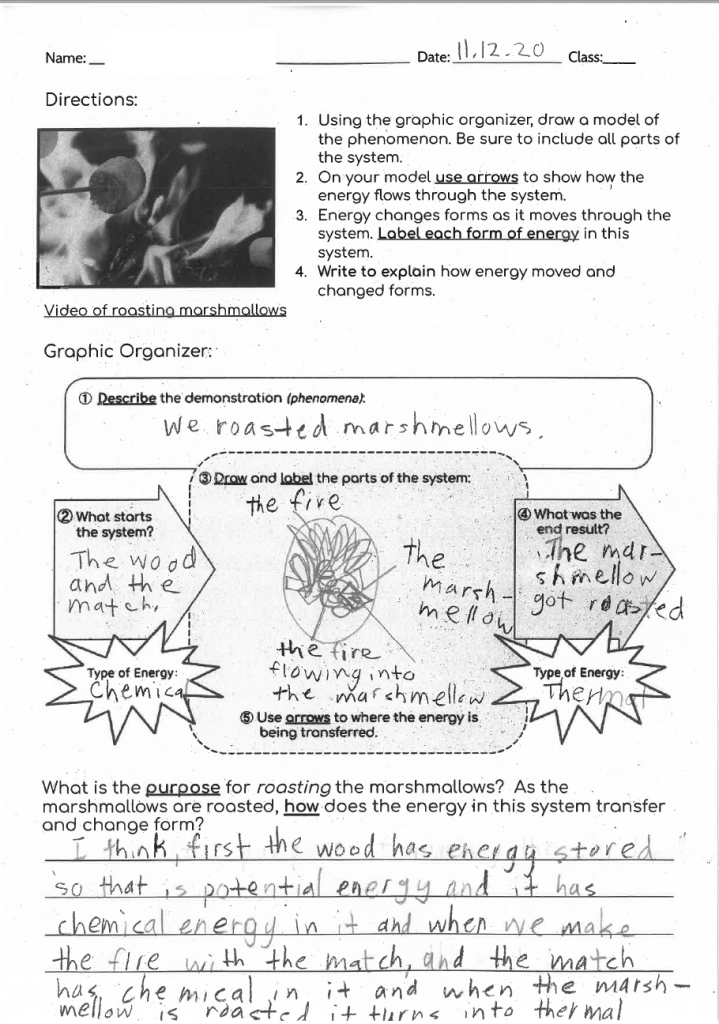

The third assessment measure was more of an experience. Our science/maker space teacher, Catherine Walton (@FIS_ES_Science), designed a graphic organizer, and our outdoor learning coach, Miriam Hilger (@maryamhilgertv1), brought the students outside to roast marshmallows. The task was for students to fill out the graphic organizer to show the transfer of energy which occurs when we roast marshmallows (The students had used the graphic organizer before, on multiple occasions). This assessment was relatively brief (two class periods), involved writing, was carried out independently, and covered outcomes 1 and 2.

The final assessment was one I like to do a lot–the one-on-one interview. I sat down with each student, and asked them four simple questions about the unit: 1) Explain the difference between potential and kinetic energy, 2) Give me some examples of potential and kinetic energy, 3) How can we use energy more responsibly?, and 4) Explain the steps of the design cycle. Which step in the design cycle do you think is the most important and why? This interview took about 2-3 minutes for each student, and was conducted while the class worked on another task which did not require my full engagement. I jotted down some notes to help me remember what the students said. This assessment was brief (two class periods), involved explaining, was carried out independently, and covered all three outcomes.

As you see, between the four assessment measures, all possible elements on the graphic organizer were covered. When it came to reporting time, I was able to look at four different measures, and I have to say, it was eye-opening for me! Some students who did really well on the energy project, did less well on the interview. Students who were unable to describe the transfer of energy during marshmallow roasting, did an amazing job putting together their energy book. I really feel like I got a comprehensive understanding of where each of my students were in their understanding of the unit. We wrapped this unit up right before reports went out, and I was able to write detailed comments about each student. I felt assured that the grades I was giving were accurate as well. Also, I only had ONE student in class who was not ‘achieving’ in this unit. I believe that when teachers give students ‘multiple opportunities for success’ they usually find that students ARE successful in at least one or two of those opportunities.

Creating multiple assessment measures for a unit is not something that necessarily happens overnight, and it is definitely unlikely that you will be able to achieve this for every unit in one school year. I encourage you to start building multiple assessments for one unit this school year. This should be a unit of inquiry for those working in an IB school, or a social studies or science unit for those working in a traditional school. Once you feel comfortable using multiple assessment measures you could also try it out with a mathematics unit. Over time, you can refine the assessments until you have three or four which cover all the elements on the graphic organizer, and which you feel give you the most comprehensive view of student understanding.

So I explained why I believe there should be no such thing as a summative assessment. I also believe that there should be no such thing as a summative assessment. By this I mean that final assessments are only final if we treat them as such. An assessment becomes formative when we use it to drive further instruction. In my mind, every assessment should be formative, because if I discover, after giving a summative assessment, that a portion of my students, or even one student, did not understand the unit, it is my job as an educator to give those students another chance, or to modify my instruction in such a way that makes it possible for every student in my class to understand the material. I would like to give you an example from a mathematics unit on number sense.

Our team started off the school year with our number sense unit, as most teams at most schools do. Number sense is really the foundation of all mathematics, and it is important that students have a strong understanding of basic number sense before moving on to other topics such as graphing, fractions, or probability. Our number unit involves whole numbers (place value, comparing, rounding etc.), adding and subtracting and number patterns. We gave a pre- assessment at the beginning of the unit, spent 6 weeks learning about number, and then gave a ‘summative’ assessment. As is usually the case, I had a range of outcomes on the summative assessment. Some students were strong at the beginning of the unit and they were still strong at the end. Some had very little understanding of number in the beginning of the year, but showed on the summative that they had learned a lot over the six weeks. There were a few students who struggled on the pre-assessment, and continued to struggle on the summative assessment. When I saw the range of student success I asked myself a few questions: 1) Was I going to leave those struggling students behind? 2) In fact, why did the learning have to stop after 6 weeks? 3) And, if we spend six weeks on a unit, and then forget about it for the rest of the school year, are the students going to retain the understandings that they built over the six weeks? My ultimate goal for every unit is for every student to make significant academic and personal growth, and if I see that is not the case, then I have to do something about it. I also want my students to understand that, as lifelong learners, when we acquire new skills or understandings, those new understandings raise new questions. Learning never has an end. Therefore, it is my practice to give students ongoing opportunities to practice the skills they learned and extend the understandings they had at the ‘end’ of a unit.

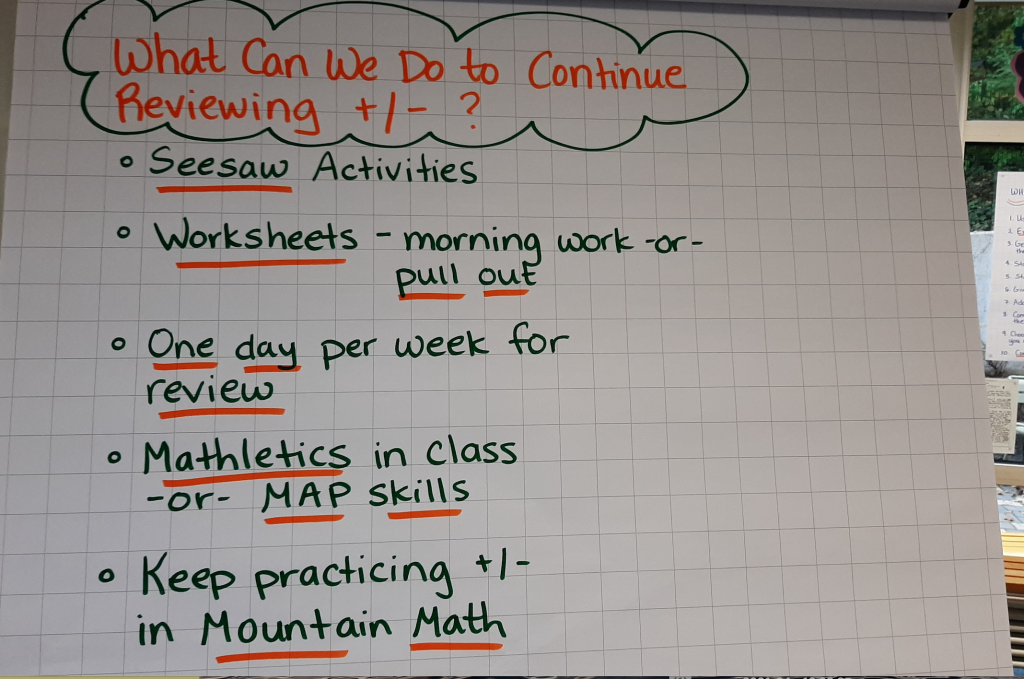

So, with that first unit on number sense, which is such an important foundation for the rest of the school year, I gave students the opportunity to extend their learning beyond the end of the unit, The first step in extending learning is self-reflection. I took a quick look at my students’ assessments when I first collected them, but I did not mark them. I consider this to be the responsibility of the students, and in fourth grade I can trust them to do this work. I handed the assessments back to the students and we went through the problems together one by one. I explained very clearly how they should mark their assessments to show which problems they understood and which they did not. After that, I shared a Google Form with the students on which they recorded their assessment outcomes. This was created by my colleague, Catherine Thornton (click this link to access the form. Please make a copy!!. This data was for me, so I could make small groups and plan for ongoing instruction. Once that was done, students took a second to jot down one success and one area for growth in their math notebook. Then, we got together as a class and brainstormed ways that we could reach our goals. As you can see from the photo below, the students’ ideas included me assigning differentiated Seesaw activities, and small group pull out work facilitated by our TA. Next, it was my turn to do some work, by planning opportunities for review and/or extension into our weekly schedule. After an additional month of differentiated review, I gave students the option of retaking the test. What I find so amazing about this approach is that it puts students in charge of their own learning, and those kids who didn;t get it the first time don’t feel defeated because they realize that the first ‘summative assessment’ was just a first attempt in learning (F.A.I.L.).

Of course, this approach may not be appropriate for every academic subject, or every unit. You have to be thoughtful about which aspects of the curriculum you can and should extend. Generally, foundational units such as number sense, or an initial reading unit which covers basic skills such as picking just right books, fluency and making predictions, are good candidates for extended review. The content should be simple enough to build it into your weekly routines, and should be relevant to what you are doing throughout the school year.

So, do you see what I mean about summative assessments? There’s just no such thing! I don’t believe in them! I wonder if any of you have strategies for making summative assessments more effective and meaningful? If so, please share them in the comments below!