Doing Pre-Assessment Right

No Such Thing As a Summative Assessment

Educators differentiate between two different types of assessment–formative and summative. Formative assessments are meant to drive instruction and help teachers differentiate for their students. Summative assessments, on the other hand, are meant to show the cumulative knowledge which a student has acquired over the course of a unit of study. Summative assessments, in their traditional form, are used to assign grades or marks, and are usually the last thing students do before moving on to the next unit of study. But what if there was no such thing as a summative assessment?

‘What if there was no such thing as a summative assessment?‘

I want to stress two different aspects of this statement. Firstly: There is no such thing as a summative assessment. What I mean by this is that assessment of student understanding can (and should) take multiple forms. The typical paper-based summative assessment is already being challenged, and rightly so. This is a format that many students have difficulty with. If you were to sit down and talk with one of these students they would likely be able to tell you all sorts of things about the topic at hand–geometry, states of matter, character motivations–however, they freeze up the moment you place the assessment in front of them. This is because paper based tests often involve a series of instructions, and require some writing. In this case, what’s really being assessed is the students’ ability to read and write, and if you are assessing a unit of inquiry, or a social studies or science unit, you could be missing a large chunk of what that student actually understands. You are probably already thinking of a few students in your classroom because when you get their assessment back you think to yourself ‘I know she could have done better’. In fact, when it comes to reporting time you might just bump that student’s grade up because you instinctively know that she was capable of more. However, the same thing might occur with another student when it comes to a summative project, a presentation, or a portfolio. I’m not going to give you the whole spiel about learning modalities, but suffice it to say that current research has proven that students do not learn in different ways (see this article for a discussion of learning modalities.). However, students are capable of SHOWING their learning in different ways and to different degrees. To get the most accurate view of a student’s understanding of a unit, we need to offer them ‘multiple opportunities for success’.

‘To get the most accurate view of a student’s understanding of a unit, we need to offer them multiple opportunities for success.’

When I design, or choose, summative assessment measures, I base my choices on three important aspects:

- Time

- Modality/Subject

- Independence/Collaboration

TIme is taken into consideration for the simple fact that it is limited. I want to give my students multiple opportunities for success, but I can’t fit in four lengthy and involved summative assessments. Therefore, I need to make sure that a couple of the assessments are quick and easy. These could take the form of an exit slip, or an interview.

I use the term ‘modality’ to describe the way in which students show their understanding. These are not the supposed learning modalities that we are all familiar with (kinesthetic, visual, auditory, tactile), but different approaches that the student takes in presenting their knowledge. This is important to consider for the reasons already stated–some students may be more capable of explaining their understanding in writing, while others may find more success in building a model or giving a presentation.

The level of independence or collaboration is considered because we need to ascertain whether students are capable of demonstrating understanding in both contexts. Some students work well in a group, and are able to synthesize their understandings with those of their peers. Other students do their best work when they have the chance to extend their thinking on an individual basis.

Finally, the final assessments should cover all lines of inquiry or outcomes. Not every measure needs to cover all the outcomes, but each outcome should be addressed in some way, through at least one, or more, of the assessments. This is another reason I like to give multiple assessments; because it is nice to focus each assessment on a limited number of outcomes. This makes the assessments more clear for the students.

I have created the graphic below to show how these different elements merge to create diverse types of assessment experiences for students. The ideal situation would be to cover each subelement in some way through one of the assessment measures.

| Time | Modality/Subject | Independence/Collaboration | Outcomes |

| Time Intensive | Read/Write | Independent | Outcome 1 |

| Brief | Draw | Partners | Outcome 2 |

| Present | Small group | Outcome 3 | |

| Create | Outcome 4 | ||

| Explain (oral) |

As an example, let me share with you the summative assessments I gave my students for our grade 4 unit on energy. Now, I can’t take credit for all of these, as I just joined the grade 4 team this school year, and a couple of these assessments were already in place when I came on. The central idea for this unit is: Humans use their understanding of the different forms of energy to create and innovate. The lines of inquiry, or desired understandings are: 1) The forms of energy (kinetic and potential), 2) How energy is stored, transferred and conserved, as it relates to electricity, and 3) How we use our understanding of energy to create and/or design (the design cycle).

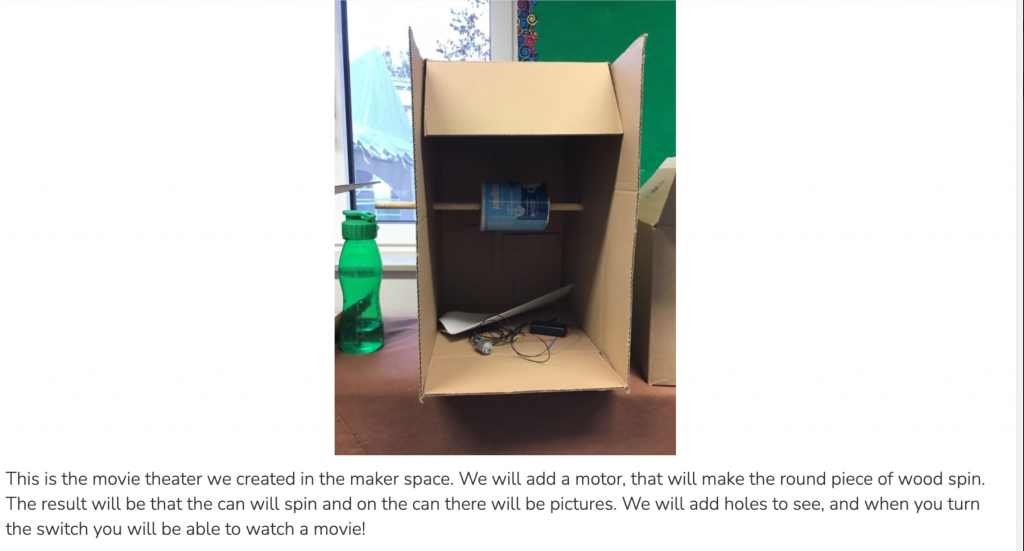

The first assessment was a collaborative energy project. Groups of students were given the task of building something which would demonstrate at least two different types of energy (some type of potential energy and some type of kinetic energy). Once the project was complete, they recorded themselves on Seesaw explaining the different types of energy, how the energy was transferred, and the challenges and successes the group experienced while working through the design cycle. This project was time intensive, involved drawing, creating, and presenting, was carried out by small groups, and covered all three outcomes.

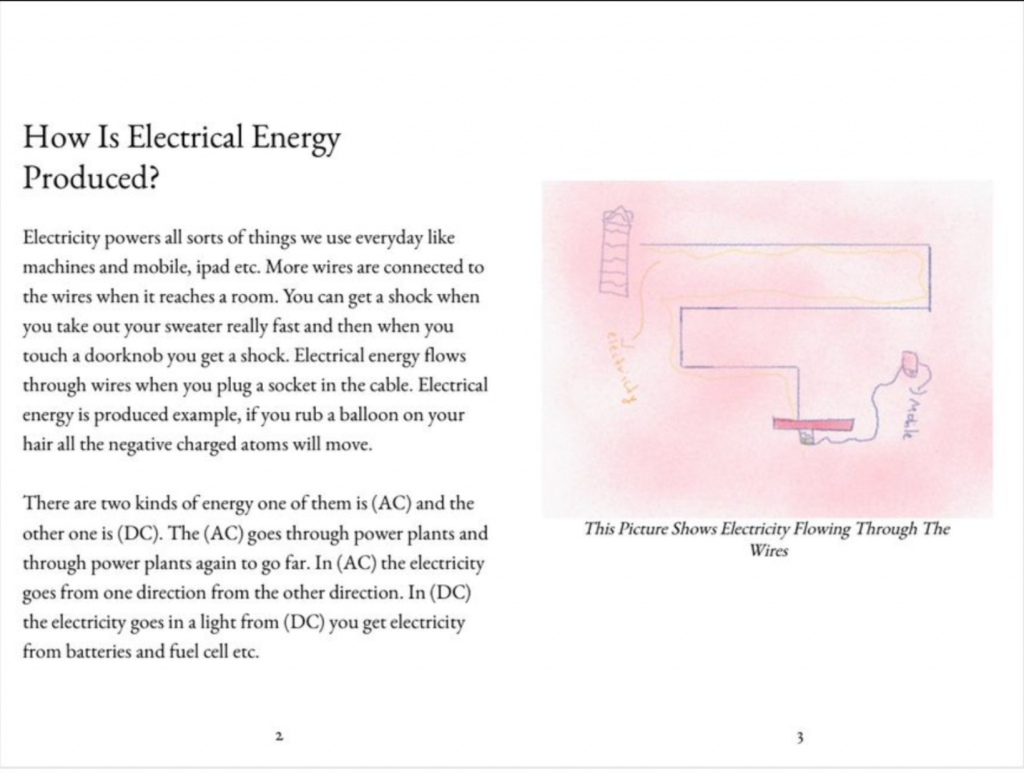

The second assessment was an energy book which was written and designed by groups of students. This project connected to our reading workshop unit on informational texts. Students read and took notes on an energy topic over a number of weeks. They then learned how to turn their notes into paragraphs. Finally, they worked with their group to synthesize their learning into a book, adding an introduction and conclusion, as well as text features. This assessment measure was time intensive, involved reading and writing, was carried out independently and in small groups, and covered outcomes 1 and 2.

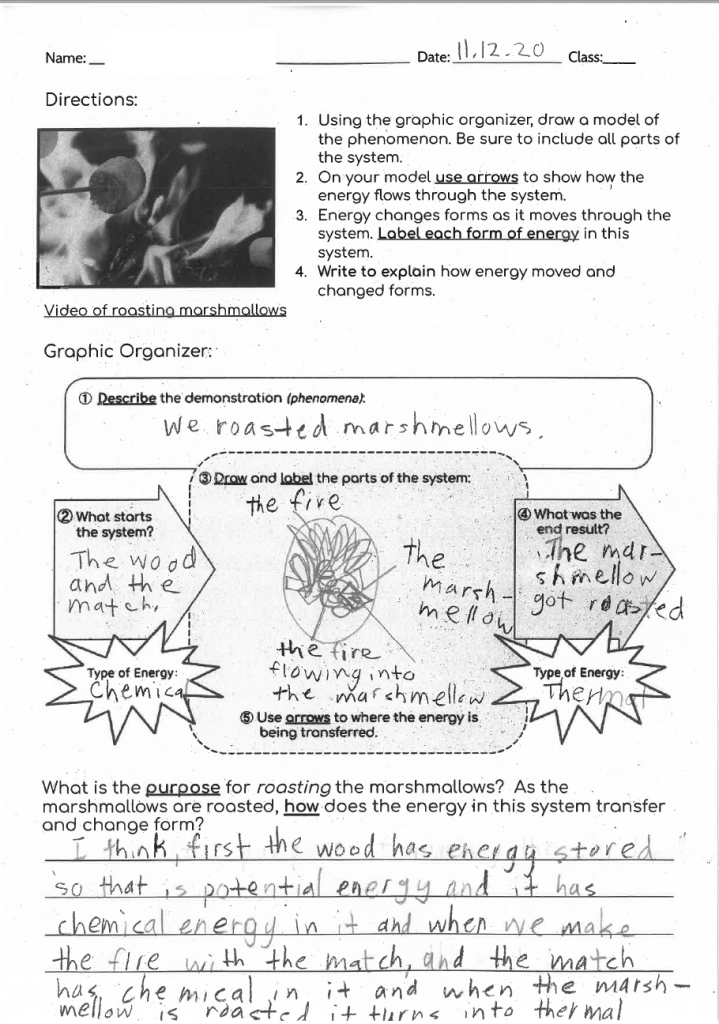

The third assessment measure was more of an experience. Our science/maker space teacher, Catherine Walton (@FIS_ES_Science), designed a graphic organizer, and our outdoor learning coach, Miriam Hilger (@maryamhilgertv1), brought the students outside to roast marshmallows. The task was for students to fill out the graphic organizer to show the transfer of energy which occurs when we roast marshmallows (The students had used the graphic organizer before, on multiple occasions). This assessment was relatively brief (two class periods), involved writing, was carried out independently, and covered outcomes 1 and 2.

The final assessment was one I like to do a lot–the one-on-one interview. I sat down with each student, and asked them four simple questions about the unit: 1) Explain the difference between potential and kinetic energy, 2) Give me some examples of potential and kinetic energy, 3) How can we use energy more responsibly?, and 4) Explain the steps of the design cycle. Which step in the design cycle do you think is the most important and why? This interview took about 2-3 minutes for each student, and was conducted while the class worked on another task which did not require my full engagement. I jotted down some notes to help me remember what the students said. This assessment was brief (two class periods), involved explaining, was carried out independently, and covered all three outcomes.

As you see, between the four assessment measures, all possible elements on the graphic organizer were covered. When it came to reporting time, I was able to look at four different measures, and I have to say, it was eye-opening for me! Some students who did really well on the energy project, did less well on the interview. Students who were unable to describe the transfer of energy during marshmallow roasting, did an amazing job putting together their energy book. I really feel like I got a comprehensive understanding of where each of my students were in their understanding of the unit. We wrapped this unit up right before reports went out, and I was able to write detailed comments about each student. I felt assured that the grades I was giving were accurate as well. Also, I only had ONE student in class who was not ‘achieving’ in this unit. I believe that when teachers give students ‘multiple opportunities for success’ they usually find that students ARE successful in at least one or two of those opportunities.

Creating multiple assessment measures for a unit is not something that necessarily happens overnight, and it is definitely unlikely that you will be able to achieve this for every unit in one school year. I encourage you to start building multiple assessments for one unit this school year. This should be a unit of inquiry for those working in an IB school, or a social studies or science unit for those working in a traditional school. Once you feel comfortable using multiple assessment measures you could also try it out with a mathematics unit. Over time, you can refine the assessments until you have three or four which cover all the elements on the graphic organizer, and which you feel give you the most comprehensive view of student understanding.

So I explained why I believe there should be no such thing as a summative assessment. I also believe that there should be no such thing as a summative assessment. By this I mean that final assessments are only final if we treat them as such. An assessment becomes formative when we use it to drive further instruction. In my mind, every assessment should be formative, because if I discover, after giving a summative assessment, that a portion of my students, or even one student, did not understand the unit, it is my job as an educator to give those students another chance, or to modify my instruction in such a way that makes it possible for every student in my class to understand the material. I would like to give you an example from a mathematics unit on number sense.

Our team started off the school year with our number sense unit, as most teams at most schools do. Number sense is really the foundation of all mathematics, and it is important that students have a strong understanding of basic number sense before moving on to other topics such as graphing, fractions, or probability. Our number unit involves whole numbers (place value, comparing, rounding etc.), adding and subtracting and number patterns. We gave a pre- assessment at the beginning of the unit, spent 6 weeks learning about number, and then gave a ‘summative’ assessment. As is usually the case, I had a range of outcomes on the summative assessment. Some students were strong at the beginning of the unit and they were still strong at the end. Some had very little understanding of number in the beginning of the year, but showed on the summative that they had learned a lot over the six weeks. There were a few students who struggled on the pre-assessment, and continued to struggle on the summative assessment. When I saw the range of student success I asked myself a few questions: 1) Was I going to leave those struggling students behind? 2) In fact, why did the learning have to stop after 6 weeks? 3) And, if we spend six weeks on a unit, and then forget about it for the rest of the school year, are the students going to retain the understandings that they built over the six weeks? My ultimate goal for every unit is for every student to make significant academic and personal growth, and if I see that is not the case, then I have to do something about it. I also want my students to understand that, as lifelong learners, when we acquire new skills or understandings, those new understandings raise new questions. Learning never has an end. Therefore, it is my practice to give students ongoing opportunities to practice the skills they learned and extend the understandings they had at the ‘end’ of a unit.

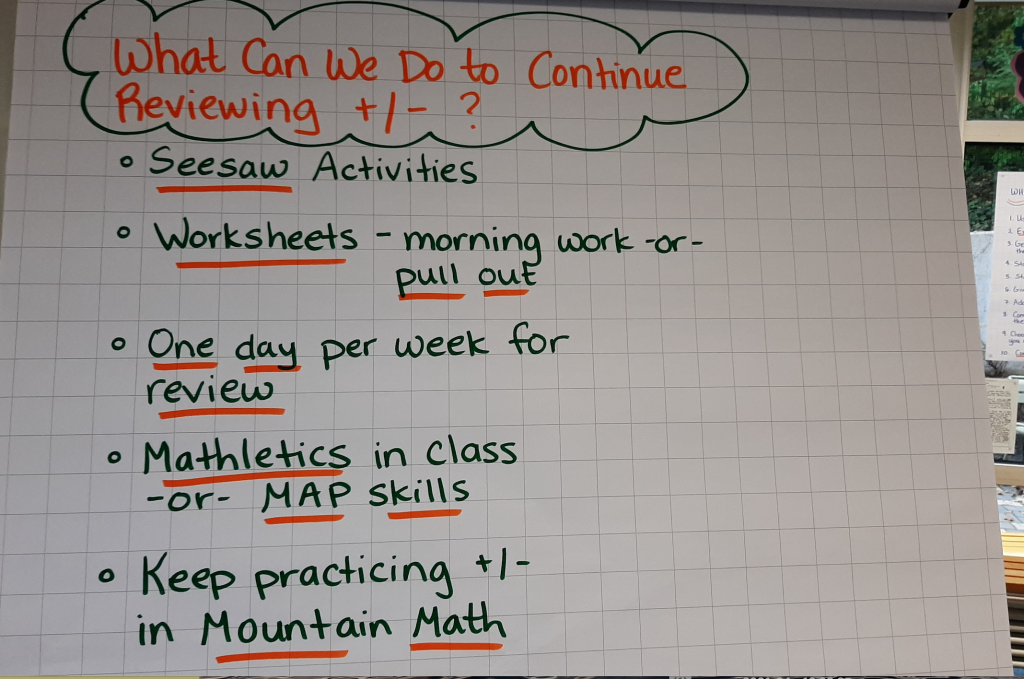

So, with that first unit on number sense, which is such an important foundation for the rest of the school year, I gave students the opportunity to extend their learning beyond the end of the unit, The first step in extending learning is self-reflection. I took a quick look at my students’ assessments when I first collected them, but I did not mark them. I consider this to be the responsibility of the students, and in fourth grade I can trust them to do this work. I handed the assessments back to the students and we went through the problems together one by one. I explained very clearly how they should mark their assessments to show which problems they understood and which they did not. After that, I shared a Google Form with the students on which they recorded their assessment outcomes. This was created by my colleague, Catherine Thornton (click this link to access the form. Please make a copy!!. This data was for me, so I could make small groups and plan for ongoing instruction. Once that was done, students took a second to jot down one success and one area for growth in their math notebook. Then, we got together as a class and brainstormed ways that we could reach our goals. As you can see from the photo below, the students’ ideas included me assigning differentiated Seesaw activities, and small group pull out work facilitated by our TA. Next, it was my turn to do some work, by planning opportunities for review and/or extension into our weekly schedule. After an additional month of differentiated review, I gave students the option of retaking the test. What I find so amazing about this approach is that it puts students in charge of their own learning, and those kids who didn;t get it the first time don’t feel defeated because they realize that the first ‘summative assessment’ was just a first attempt in learning (F.A.I.L.).

Of course, this approach may not be appropriate for every academic subject, or every unit. You have to be thoughtful about which aspects of the curriculum you can and should extend. Generally, foundational units such as number sense, or an initial reading unit which covers basic skills such as picking just right books, fluency and making predictions, are good candidates for extended review. The content should be simple enough to build it into your weekly routines, and should be relevant to what you are doing throughout the school year.

So, do you see what I mean about summative assessments? There’s just no such thing! I don’t believe in them! I wonder if any of you have strategies for making summative assessments more effective and meaningful? If so, please share them in the comments below!

A Take Away From Distance Learning: Digital Sub Plans

Using Pre-Assessments to Differentiate Writing Instruction

Video: Feedback Types

Making Feedback Count

Teacher feedback has been on my mind a lot lately. I guess it’s because, with distance learning, feedback has become even more important than before. I only see my students for an hour or two a day, but I see a lot of their work. Feedback has become sort of like a conversation for us, which has been great. I’ll make a comment on an activity, and a student will write back asking for clarification, or explaining what they meant, or giving more information. This has given me the opportunity to reflect on the quality of the feedback I am giving as well as the form it takes. As I examined my feedback I realized that many of my comments do not serve their purpose, which is to have a positive impact on student learning and attitudes. So now I’m asking myself, how are students receiving the feedback I am offering, and how can I make it better, kinder and more impactful?

After a lot of research and reflection, I have come up with three aspects of feedback that I feel are most impactful, and need to be considered:

- The type of feedback we are offering

- The approaches and resources which help students apply feedback

- The manner in which we communicate feedback

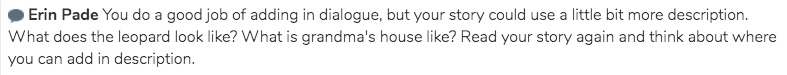

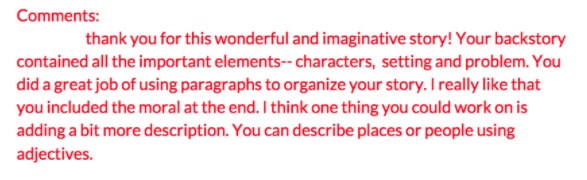

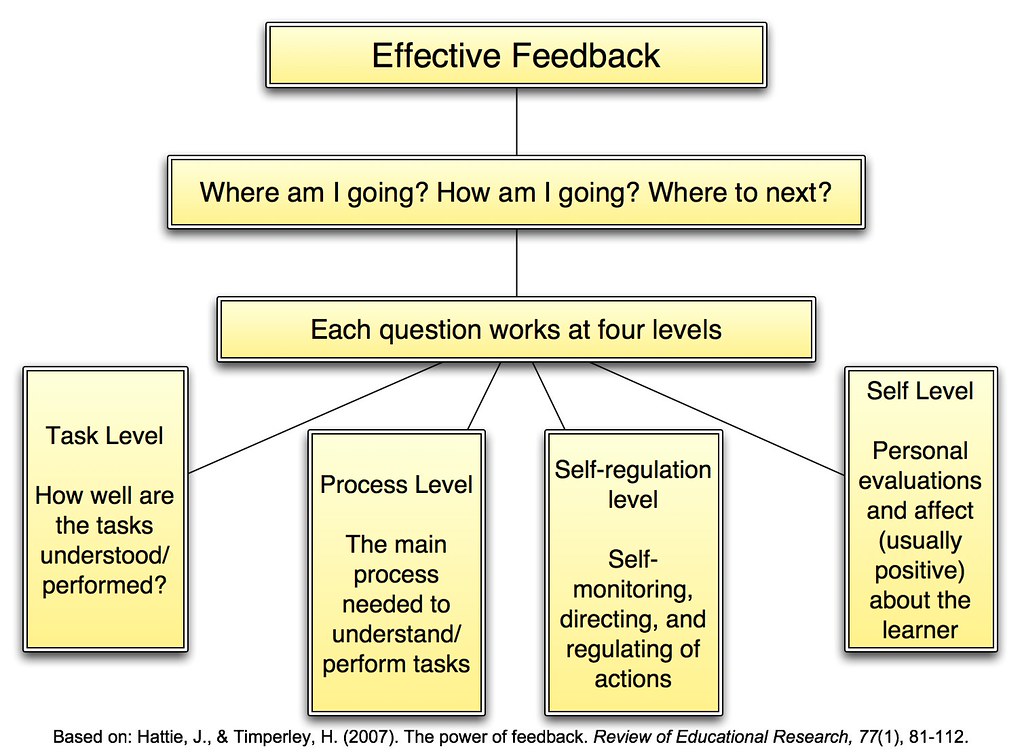

So, the first factor I’ve been considering is the type of feedback I’m giving. A 2007 meta analysis by Hattie and Timperley examined feedback types which led to the development of a feedback model. This model organizes feedback types into four categories: task, process, self-regulation, and self. Self-regulation feedback is connected to self-assessment. These are the reflections that students write about their own learning. For example, “I had a hard time focusing on the activity. Next time I will find a quiet place to work”. These types of comments don’t figure into teacher feedback, and therefore will not be considered here in terms of effectiveness. Task feedback tells whether the work was correct or incorrect, sufficient or deficient. Examples of this type of feedback are “Your story could be a bit longer”, or “You used a lot of interesting vocabulary”. Process feedback focuses on the processes or strategies underlying the task. For example, “Make sure to develop a clear plan before drafting your next story“, or “Watch the video on ‘painting a picture with words’ again. It will show you how you can add adjectives into your piece so it is more descriptive”. Finally, self feedback is non-specific praise such as, “Great job on this!” or “Keep up the good work!”. As you might have guessed, when it comes to teacher feedback, process feedback is most effective if the purpose of the feedback is formative, because it doesn’t just tell students what they can improve, it gives them guidance as to what steps they can take in order to make improvements. Self feedback does little to help students move to the next level of understanding or to improve their product. This seems quite obvious, but if we really take the time to examine the feedback we are giving students we will notice that ‘task’ and ‘self’ comments predominate the content of our comments, especially when we feel like a student has done an exceptional job, and we aren’t sure what other feedback we can offer. Why should we avoid these types of feedback? Is there anything wrong with saying “Great job!”?

Well, there are two very important reasons why we should avoid this type of feedback. The first is that students will model their own comments on those of the teacher. If you have ever engaged your students in peer assessment in the classroom you have seen quite a few ‘self’ feedback comments. “I like your story!” “This was fun to read!” “I think you could do better”. In fact, a study by Harris, Brown & Harnett (2014, accepted) examined self- and peer-assessment feedback comments written by students between the ages of 10 and 15, and found that 79% of comments were ‘task’ or ‘self’ comments, whereas only 16% were process comments and less than 5% were self-regulation comments. Of course, giving good, effective feedback is challenging, especially for students, who cannot be considered content experts, however, teacher modelling certainly plays some role in the prevalence of less effective feedback comments.

Another important reason to avoid ‘task’ and ‘self’ feedback is growth mindset. We want students to focus on learning not achievement. When we give comments such as “This was an excellent piece of work” we are sending the message that what’s important is producing something flawless or excellent, when what we want our students to focus on is growth and next steps. Therefore, the best feedback addresses the growth that the student has made thus far, areas for further growth, and advice on how the student can close the gaps in their understanding. Hattie and Timperley suggest that teachers keep three questions in mind when formulating feedback comments for students: 1) Where am I going? (what is the goal?) 2) How am I going? (what progress is being made toward the goal?), 3) Where to next? (What activities need to be undertaken to make better progress?).

“If we go in with the assumption that every student wants to do their best, and wants to produce high quality work then we have to ask ourselves what conditions and expectations are preventing students from applying feedback”.

Another consideration in terms of feedback is the approaches and resources which help students apply feedback. Just because we give thoughtful feedback on an assignment doesn’t mean a student is going to utilize that feedback. We need to consider why this might be. If we go in with the assumption that every student wants to do their best, and wants to produce high quality work then we have to ask ourselves what conditions and expectations are preventing students from applying feedback. Drafting feedback is a time-consuming endeavor, and we also don’t want to spend valuable time writing comments that will go nowhere.

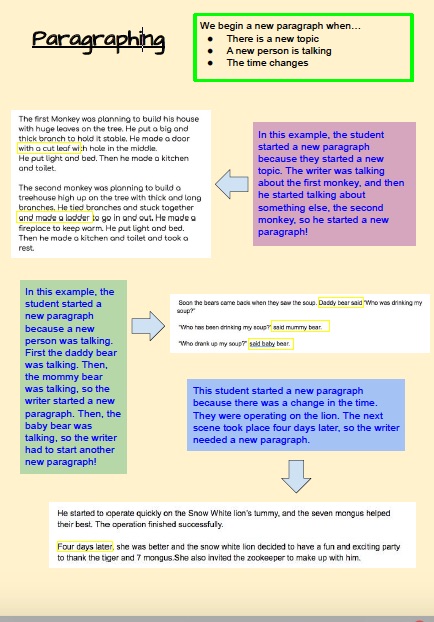

One reason students may not respond to feedback is that the feedback is too comprehensive and therefore overwhelming to the student. Think about any writing unit as an example. We did a recent unit on writing fairy tales, and the rubric we developed for this unit consisted of four outcomes for structure, two outcomes for development, and four for language conventions. Now, this is helpful for teachers when grading student writing, but If I were to hand a student this rubric they would likely be confused. This is also the case when offering written feedback without a rubric. Too many comments can make the task of revising seem impossible, especially for younger students and struggling writers. The key here is to focus on one thing at a time. Once you’ve seen a couple of samples of a student’s writing, you can determine the aspects which the student needs to work on most. Choose ONE of these aspects. Perhaps a student needs to improve at adding details to their story. Perhaps the student doesn’t have any strategies for fixing up spelling. Maybe they need help with paragraphing. When offering feedback, focus on the one aspect that the student needs the most help with for the time being, and give detailed feedback about that one aspect. Conference with the student, help them identify this as their goal, and give them opportunities to work on that goal all throughout the unit. If at any time you feel they have mastered that one goal, move on to the next one. For some students you may have to focus on one skill for the entire school year. But, isn’t it better to give them the time to focus on that one goal, and have success, than to give them a bunch of different things to focus on and see no results? When a student has a clear, simple goal, they can put all their focus and energy into that goal.

Another reason students may not accept or utilize feedback is that they haven’t developed a growth mindset. Having a growth mindset means that students believe that their abilities can be developed through dedication and hard-work. Students who have a fixed mindset believe that intelligence or ability are innate, and that achievement is more important than growth. These students may view feedback as a criticism of their intelligence or abilities. Accepting feedback means acknowledging their weaknesses, which can be emotionally challenging for some. So, how do we help develop a growth mindset in students when it comes to feedback? One way is to show examples of student work that demonstrate growth. Show an initial draft of a piece of writing, the feedback comments on that draft, and the changes that the student made to improve the piece. Another way is to offer consistent praise to students for applying feedback. Rather than pointing out the things that a student has done well, point out the improvements they have made and celebrate a student’s efforts rather than their accomplishments. Finally, give students the opportunity to give you feedback. Write along with students, show them your work on a regular basis and ask for their opinions. Model a growth mindset by showing appreciation for their feedback, and applying it in your own work.

“In order for self-regulation feedback to be effective, we need to have resources in place that the students can turn to for help”.

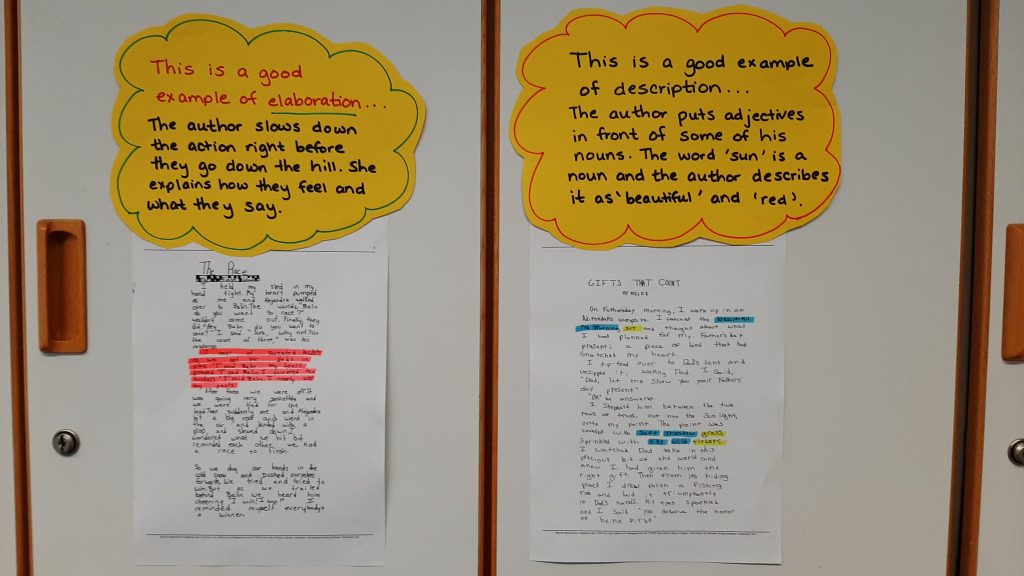

Another important thing to consider is whether there are resources available which will support the student in working toward their goal. While we would like to work with each and every student, this is impossible in a classroom of twenty or more. In middle and high school, students are expected to revise independently (although many of them are not ready for this), however elementary students lack experience. They don’t know where to go to get help. This is why process feedback is so important. We need to tell students not only WHAT they can improve in, but also HOW they can improve in it. But, in order for process feedback to be effective, we need to have resources in place that the students can turn to for help. An example of this is exemplars. Most teachers show students exemplars of ‘good writing’, and point out what makes the writing good. This is so much more powerful than just telling a student what a good piece of writing should have. Why not make these exemplars available to students all the time? You could have a folder containing exemplar pieces which relate directly to each outcome, or they could be posted on the wall.

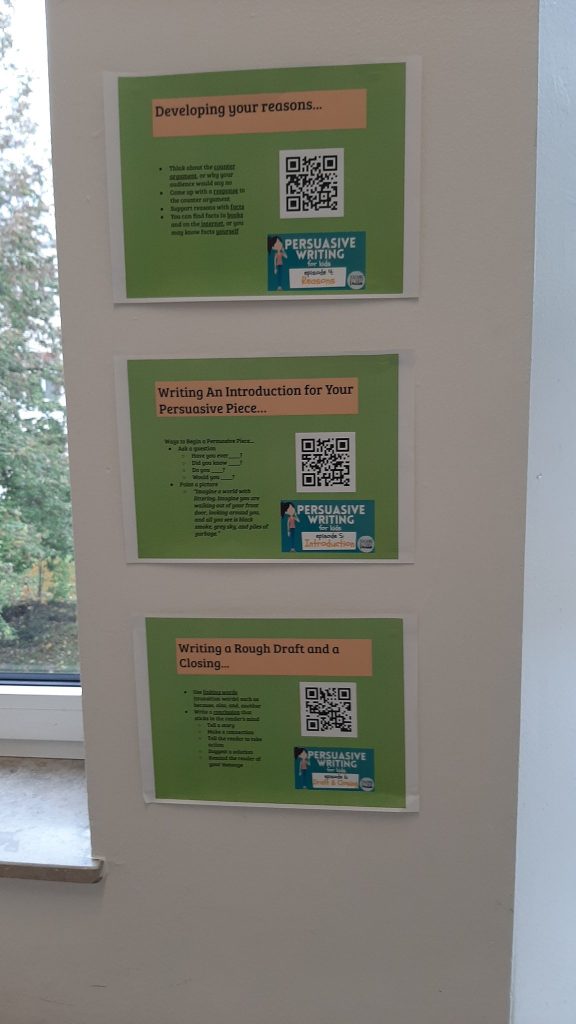

You could even record yourself reading an excerpt from an exemplar and pointing out the skill that you want students to focus on in that piece and have these recordings available to students. In my opinion, it is better to have multiple examples of good student writing, which each highlight one outcome than to show a ‘good’ piece of writing and point out all the things the writer is doing well. I can imagine how overwhelming this might feel for a student, who suddenly is supposed to notice several skills which they might not possess themselves. Another possibility is to make instructional videos available to students. I got a great idea from a colleague of mine who created posters with QR codes which linked to instructional videos. Post these in the classroom where the students can access them independently. If a student needs help with writing a powerful introduction, for example, you can direct them to the instructional video about this skill.

We also had a visitor from The Columbia Readers and Writers Project who showed us a really good idea. She had created a folder organized by subtopic which had a page dedicated to each outcome. Each page had examples, explanations and images for the outcome. She had created this folder as a teaching tool which she could use during small group instruction, but it could also be a resource that students could refer to independently. While this is a time-consuming undertaking, it is one of those things which, when it is done, becomes an invaluable resource. It is also something you can add to as the year goes on, and then you can have a finished product at the end of the school year which you can continue to utilize in the coming years. A team of teachers could take one or two pages each and make copies of these so every team member could have a folder of their own. Of course, it is important that you model for students how to use these resources so that they can be successful. Students need to be sure about where they can go for help and how to use the resources. They are already facing some challenging work with trying to learn a new skill; we don’t want to add the extra challenge of trying to access a resource that is not clear and user-friendly.

Finally, we need to consider The manner in which we communicate feedback. Naturally, feedback needs to be comprehensible to a student, and a comment may not be understood for several reasons. Perhaps that student is a beginning reader, or a language learner, or maybe the vocabulary is too challenging. When we offer feedback to a student we need to keep the student in mind. There’s no point in writing comments that we’re just going to have to explain later. If feedback is written, it needs to, of course, be in simple, kid-friendly language. But, what if that student is a struggling reader or an EAL student? In that case, even clear, simple feedback may be incomprehensible. Just the fact that the student doesn’t understand the feedback in the first place may produce a lot of anxiety and self-doubt. Are there other, better ways of offering feedback so that it is clear the first time?

Well, I have always loved conferencing with students. This is a routine that is built into the readers’ and writers’ workshop. It is helpful to sit down with a student one-on-one to talk about their work and offer feedback. The advantage here is that there are a lot of body and facial cues which help you determine whether a student is understanding what you are saying or not. When you feel like the student is not understanding, you can say it a different way. The student can ask questions. You can refer directly to specific places in the text. You can point the student in the direction of resources that they can use to help them revise their work. But, let’s be honest; realistically, we can only see three, at the most four, students per class period. Feedback needs to be timely. What is the rest of the class doing while you’re working with those three to four students? Another drawback to oral feedback which you don’t have with written feedback is that, unless you record what you are saying, the message gets lost. Therefore, the next time the student is working they don’t have that feedback next to them to refer back to. So, how can we combine the best of both worlds?

There is recent research on the use of audio and video feedback as an alternative to traditional methods. Granted, these studies involve older students, however, the data is pretty clear that this type of feedback is preferred by students. They say it is easier to understand, has more depth and is more personal than written feedback (Crook et al., 2012). Also, video and audio feedback have been shown to be most effective in helping students make meaningful revisions to their work (Hattie, 1999). Teachers find video and audio feedback better because they can adjust the volume and pitch of their voice to highlight specific points which aids comprehension. The added benefit of video feedback is that students can gauge the reactions of the teacher through body language and facial expressions; this aspect also makes the feedback easier to understand. Additionally, audio and video feedback are recorded, so they can be accessed again by students.

So video feedback is an option that maybe you want to try out. It is more personal, more emotive and more effective. The only thing that’s missing is the interaction that we gain through conferencing. Perhaps a mixture of conferencing and video feedback would be the answer. The other option is to video your conferences with students and share those with them.

Distance learning has been an opportunity to try out new strategies for offering effective feedback. As we move back into the classroom we should consider which aspects of this we can and should retain. I’m curious to hear which feedback strategies you’ve tried out in recent months. Is there anything that has worked really well? Which new strategies would you like to try out? Do you have any additional examples of effective feedback strategies? Please, share your ideas in the comments!!

Assessment and Distance Learning

In this new dawn of distance learning, teachers have many questions, not the least of which is: Am I still delivering the best possible instruction to my students? Tangent to this is the question: How do I know whether I am still delivering the best possible instruction? The simple answer to that question is: Assessment. But making effective, meaningful assessment function in a digital learning environment seems to be anything but simple. There are so many new factors we need to consider when designing and administering assessment online. Firstly, what form does it take? Paper assessments are out of the question. Big, summative projects are fine, but we won’t be there to guide them every step of the way, and help them reflect. This leads to another question: Does the form of the assessment match the content and the desired outcomes? This is easy to resolve in a classroom environment, as we can choose from a wide range of possibilities, however, online learning limits our choices. An additional concern is whether or not students are completing the assessment on their own, or whether they’re getting help. Once the assessment leaves the four walls of the classroom we have no control over how it’s handled.

“I actually see this as an opportunity; an opportunity to weed out the unnecessary and time-consuming aspects of assessment, and pare things down to the real, essential approaches which will make assessment quick, easy and accurate”.

So, what is clear is that we are going to have to rethink the way we do assessment right now. This isn’t to say that we should completely reinvent the wheel; nobody has time for that, nor do we need to. Not to mention, this distance learning thing won’t last forever. As hard as it may be to believe it, we will be teaching in regular classrooms again in the near future. Therefore, I’m not suggesting we think of assessment differently. I’m suggesting we should think carefully about how we can use what we know about assessment already in order to elicit the best possible understanding of our students’ grasp of instruction in a digital learning environment. And key is that it remains SIMPLE. If every other teacher’s life is anything like my life then it involves a full day of recording videos, assigning tasks, checking tasks, and having Zoom meetings, all while tending to my own family and personal business. I cannot be spending hours developing assessment measures. I actually see this as an opportunity, an opportunity to weed out the unnecessary and time-consuming aspects of assessment, and pare things down to the real, essential approaches which will make assessment quick, easy and accurate. Therefore, I’ve put together a short menu of SIMPLE formative and summative assessment approaches that I feel lend themselves very well to distance learning, and which solve many of those challenges which an online learning environment creates:

- Keep it formative from the start

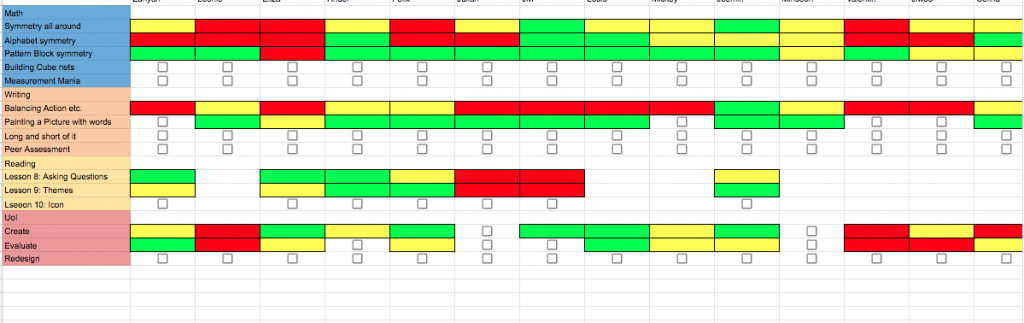

This was a suggestion from a colleague of mine. She designed a checklist on Google Sheets which we use to keep track of the assignments students have completed. This is useful in so many ways. Not only can you see which students are completing assignments, and which are not, so you can offer support to those students who seem to need it, you can also see if there was a specific activity that many students didn’t finish, or a day on which many students didn’t finish all assignments. This can help us reevaluate the types of tasks we are assigning and whether they are appropriate or comprehensible, as well as whether the amount of work we are assigning is achievable by the majority of our students. The important thing is that we use this information. If we see that students were unable to complete four assignments in one day, we can reduce it to three per day. If we notice that a good percentage of students didn’t complete the reading assignment, we can check in with the whole class, or just that group of students to determine what the roadblocks were; then we can plan follow-up instruction based on what we learn. Another idea (from the same colleague) was to give a value to each assignment completed. This could be a number value, a descriptor, a symbol of some sort, or a color, such as I used in my example here. These values indicate whether a student had a strong understanding of the concept, a developing understanding, or a beginning understanding. Of course, I then need to use this information to plan instruction. I wouldn’t suggest that teachers completely differentiate the activities they are assigning; that would be far too much work. But you can schedule a Zoom session with a small group of kids, assign mentors, or assign additional review to those students who need it. Adding values to your checklist is also going to be very helpful when it comes to reporting time. Of course, as you continue to work with students, you can go back and change the values to reflect their growing understanding, so that when you report you have an accurate picture.

2. Conferencing and interviews

One big challenge of distance learning is knowing whether students have been completing assessments on their own. This can easily be remedied through conferencing and interviews. Conferencing is familiar to anyone who does readers’ and writers’ workshop, but it can also be done with mathematics, social studies or science. Just prepare a few simple questions, and set up a conference time with a single student or a group of students. Below is an example of some questions which I asked students for our readers’ workshop unit on biographies. These were designed to identify different levels of understanding. Of course, I also created a recording sheet on which I could keep track of what the students were saying, and any notes that would help guide me as the unit continued.

Biography Questions:

1. What is the subject of your biography like? What are their traits? Can you give examples of this?

2. When/where did your character live? Can you tell me about that place/time?

3. What do you think is the big theme or message in this story?

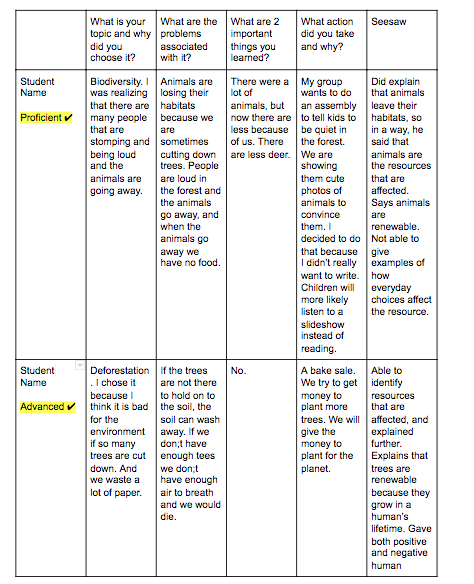

This strategy also works for summative assessments. I once tried this out in the classroom for our unit of inquiry on natural resources. You can see some of my questions and the students’ answers below. Each ‘interview’ took about five minutes, but I gained a great deal of insight from how the students responded to the questions, and whether they were able to elaborate. So much non-verbal information is also communicated when you meet with students face-to-face. A final advantage is that you are assessing exactly what you want to assess, whereas paper and pencil assessments may be truly capturing their competency in reading and/or writing, and group projects may only reflect the efforts of the strongest member of the group.

3. Using Web Features to Assess

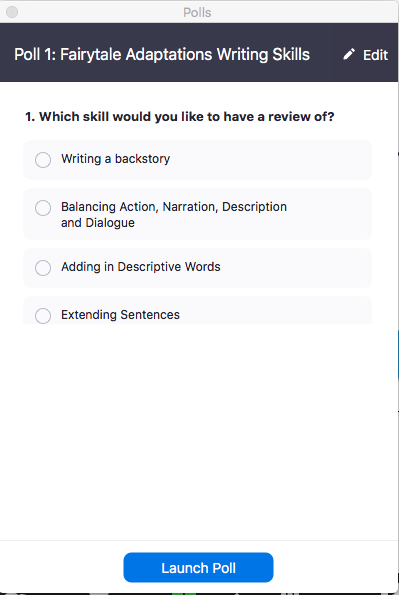

Many teachers are using Zoom right now, or a similar web-based platform, to hold meetings with students. These platforms have many features that allow you assess students quickly and easily. One feature on Zoom that I have gotten a lot of use out of is the polling feature. You can create a quick poll on any topic, and see the results of the poll in a spreadsheet. For example, I created a poll asking students which writing skill they would like to have a review of for our unit on Fairytales (see below). This helped me determine whether I needed to do another whole class lesson on a specific skill, or whether I should break the students into small groups and revisit various skills with those groups.

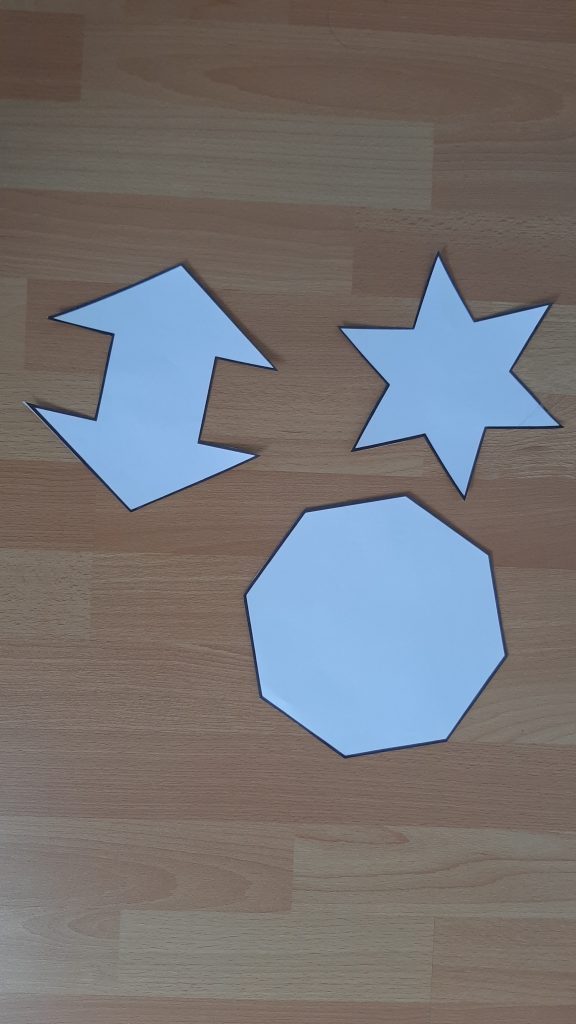

The chat feature can also be used to assess students quickly. Think of it as a mini-whiteboard exercise. I used this feature the other day to determine where my students were in their understanding of symmetry. I first did a quick review of symmetry using some cut-and-fold shapes. Then, I held up some shapes, one at a time, and asked kids how many lines of symmetry each one has. I told them to write their response in the chat. I was able to quickly see that most of my students understood the concept, but that several needed an extra review. I met with these students the following day.

Google also has many features that are helpful when assessing students during distance learning. Google Forms is one of those that I have used a lot. In the past I have used it as a self-assessment tool for writing or unit of inquiry. For the writing unit I just entered the various criteria that we were hoping to meet. For example ‘I wrote a beginning which helped readers know who the characters were and what my setting was in the story’. The students looked at their piece of writing and rated themselves using the descriptors ‘not yet’, ‘starting to’, or ‘yes’. The great thing is that once they had all finished, I got the data in an easy to read graph. I was then able to use this information to plan for further differentiated instruction based on what the students were still working on.

I also think assessment doesn’t have to be purely academic. I recently used Google Forms to get a sense of how my class was coping with distance learning. This helped me determine whether I was assigning too much work, whether the activities were too challenging, and what I could do to make the experience easier for my students. Google Forms also allows you to see each individual response, so if you have an outlier, say a student who feels overwhelmed while the other students are doing okay, you can check in with that student to see how you can support them. There’s something about a form that makes it all easier to say somehow 🙂

4. Peer Feedback

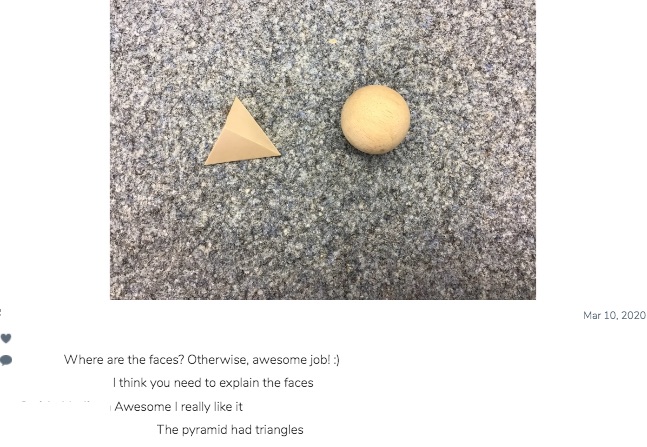

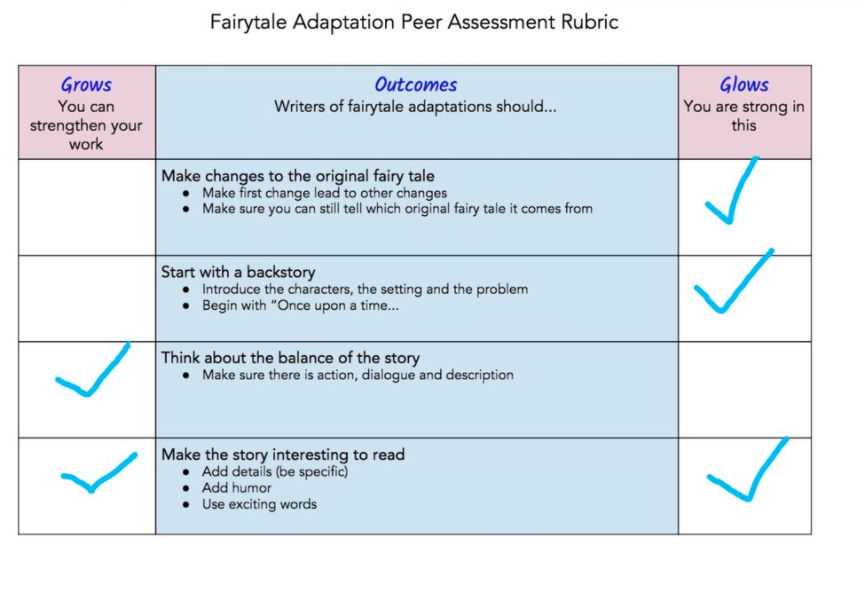

Peer feedback has so many advantages. Firstly, it saves the teacher a lot of time. Additionally, when students assess a peer’s work they are often able to recognize mistakes or areas for growth that they wouldn’t recognize in their own work. Once a student has assessed a peer’s work, they are more competent self-assessors. Finally, peer assessment helps students develop many transferrable skills. They learn to give feedback that is kind, but helpful. They learn to reflect on the desired outcomes of learning tasks. Finally, they develop a sense of agency and begin to take on more personal responsibility for their own learning. I have used peer assessment in all areas of the curriculum, and it’s perfect for distance learning because students get a chance to work with their classmates, and see examples of how other kids have approached a learning engagement, although they are not in the classroom. My feeling is that we need to create as many opportunities for connection as we can right now. I have a couple of examples here of how my students have peer assessed using technology. The first one was a math activity we did on Seesaw for our shape and space unit. I wanted the students to have an opportunity to reflect on their learning about 3D shapes before taking the final assessment. I had each student take a photo of two 3D shapes, and then explain their understanding. Then I put the students in groups of three, and each student had to write comments on the other two students’ Seesaw post. My second example is a writing assignment which was worked on during distance learning. I had the kids type up the first half of the fairytale adaptations they were writing. At our next morning meeting we developed a rubric together based on what we had learned so far through our mini-lessons. Then I paired the students up, and had them rate each other’s writing using the rubric. They also left more specific comments on their Google Doc.

When utilizing peer assessment, don’t worry about the feedback being accurate, or being the kind of feedback you would have given. In many cases the feedback that students give each other is more relevant to them, and is in a language they can understand. Also, the type of feedback a student gives tells the teacher a lot about what that student does and does not understand. Finally, the academic and affective benefits of peer assessment are not just isolated to the corrections and improvements students make as a result of their peer’s feedback, they are far-reaching.

5. Running Records

Conducting reading assessment during distance learning presents a bit of a challenge. At my school we use Fountas and Pinnell. In the classroom we sit side-by-side with the student with the book in front of us. The only way we can make this possible on a computer is to use a document camera to project the book so students can see it. This is not an ideal situation.

However, there is an alternative. Many websites which offer digital books are now giving out free trials. Many teachers at my school are now using Epic! We also have RAZ-Kids accounts for our ESL students. Both of these sites have the books levelled, so it is easy to find the level for the particular student you want to assess and assign a book at that level to the student. There are many blank running record sheets online that you can use, which contain generic questions for both fiction and nonfiction books (click on this link to see one I purchased from Teachers Pay Teachers).

I hope these tips have been helpful. I am certain my list does not include all the great ideas out there for how we can assess students during distance learning. Please, share your ideas, and let’s start a real conversation about this!

Why Formative Assessment?

I am really excited about assessment! It’s my thing. It’s what I’m passionate about. It may sound to you as if I need to get a life. But I’ll tell you what really gets me excited about formative assessment–it truly has the power to transform learning. It also has the power to make better teachers, which is what we’re always striving to be.

Now, I have been assessing kids ever since I’ve been a teacher. For a long time, assessment seemed like a necessary evil. I felt almost apologetic when I said to my students, “Okay, you’re going to be taking a test today”.That’s because, for me, assessment was a summative act, and was meant for reporting. Therefore, if a student did poorly, that was the grade they were going to have on their report card. It would also be a big bummer for me, as I looked at certain student’s test and wondered, “Where did I go wrong? How did I fail this kid?”

“Formative Assessment is not a tool, it’s a process”

As I became more experienced and learned more from my peers, I discovered that assessment is not one thing, it is many things. By now, you all have probably heard about the difference between assessment of learning, assessment for learning, and assessment as learning. Assessment of learning is what I was doing a lot of before. It is summative, and is mostly used for reporting. Assessment for and as learning are terms which describe meaningful formative assessment practices. According to the State Collaborative on Assessment and Student Standards for Formative Assessment for Students and Teachers (FAST SCASS) formative assessment is “[…] a process used by teachers and students during instruction that provides feedback to adjust ongoing teaching and learning to improve students’ achievement of intended instructional outcomes” (xxx). This is a very good definition of formative assessment, but this is not how I understood it for many years, In fact, I think I only caught the “a process used by teachers during instruction that provides feedback” part. I was giving formative assessments to my students, but I wasn’t using the data those assessments were providing me with to adjust instruction in a targeted way. Formative assessment seemed like a big waste of time for me, as I discovered that my students were all over the place in terms of their understanding, but I didn’t know how to differentiate to meet their needs.

It was when I began my Master’s work (recently) that I realized that formative assessment is not a tool, it’s a process. In a sense, if you are doing formative assessment right it becomes what your class does, it involves you and your students, and it never ends. I will explain more about how I set up my classroom, and my students, to make formative assessment transformative in upcoming posts, but suffice it to say that, if you want to discover the true benefits of formative assessment, you are going to have to change as a teacher. Also, your students are going to have to get used to routines that they’ve never seen before. It certainly doesn’t happen overnight, but once you have the process in place, you will be amazed at what you and your students can accomplish.

In my experience, the real key to powerful formative assessment is small group instruction and differentiation. Many teachers find this difficult. I did too, until I learned how to prepare my students, establish routines, and develop simple ways of recording data so that I could actually use it.

Also important is to not skip over the assessment as learning portion of formative assessment. I am a teacher at a PYP school, where we engage in inquiry based learning. For us, the student is the driver of learning. Harlen and Johnson claim that both inquiry-based learning and formative assessment “share the aim of students becoming increasingly able to take part in decisions about their work and how to judge its quality” (2014, p. 39). Assessment as learning is “when students personally monitor what they are learning and use the feedback from this monitoring to make adjustments, adaptations, and even major changes in what they understand. Assessment as Learning is the ultimate goal, where students are their own best assessors” (Earl, Lorna (2003) Assessment as Learning: Using Classroom Assessment to Maximise Student Learning. Thousand Oaks, CA, Corwin Press).

What is great about formative assessment, is that it can take virtually any form you, or the students, wish. It could be a traditional written test (these don’t just have to be used summatively), a quick white board response, a Seesaw post, a short exit slip, or a traffic light protocol. Formative assessment can also be simple teacher observation (although I would like to caution teachers that they need to have a simple yet effective way of checking in with students and recording their observations. Just simply observing students does not count as formative assessment). Formative assessment allows for variety, and can even be fun!

But the real point here is that formative assessment helps students learn better. Black and Wiliam did a review of over 250 research studies related to formative assessment, which revealed that “attention to the use of assessment to inform instruction, particularly at the classroom level, in many cases effectively doubled the speed of student learning” (Wiliam, loc. 835 of 4459). Personally, when I engage my class in ongoing, targeted formative assessment measures, I know my students better, I know exactly what my next steps will be, and I see greater growth across the board. I am also able to avoid nagging questions such as “how are you going to challenge my child this year?” since my process already accounts for this. When formative assessment is done well, every single student is served.

The UK Assessment Reform Group identified five elements that need to be in place in order for formative assessment to be effective:

- Effective feedback to students

- Active involvement of students in their own learning

- The adjustment of teaching to take into account the results of assessment

- The recognition of the profound influence assessment has on the motivation and self-esteem of students, both of which are crucial influences on learning

- The need for students to be able to assess themselves and understand how to improve

As I mentioned before, effective formative assessment is more like a lifestyle. Most of your students, will not have lived this lifestyle before. They are going to come up to you to ask you questions while you’re working with a small group, and you are going to have to redirect them, time after time, and keep sending the message that they are capable of working independently time after time, until they finally believe it themselves. But who can blame them?! Kids are, after all, creatures of habit. This will work in your favor in the long run, because once they buy into your new world order, they will do it better than you ever imagined.

You know who else are creatures of habit? Teachers. It is hard to adopt a new lifestyle. It is a lot of work to turn everything you’ve been doing for x amount of years on it’s head, and to effectively start over again. This is why professional development in formative assessment practices is so key. Some people believe good teachers are born; I believe good teachers are made. I believe this because I used to be a crap teacher, and now I feel pretty good about what I am doing, so I know growth is possible. However, PD needs to be deep, ongoing, and reflective. As James Popham says ““Human Behavior is tough to change, and one-shot workshops, even extremely illuminating and motivating ones, rarely bring about permanent changes in teachers’ conduct” (p.111). My opinion is that if there is one thing schools should invest in, it is formative assessment PD, but I will admit that as a teacher, not an administrator, I don’t really understand the logistics or costs involved. One possible option is to develop a teacher learning community (TLC) around this topic, which would be a small group of interested educators who would engage in long term action research around formative assessment, and share their findings with their colleagues.

I want to make one final point about formative assessment, and that is that it should be done at the classroom level. I have the benefit of working at an international private school, where externally developed standardized testing is not the norm. As a teacher, I am given the power to develop my own formative assessment measures, based on what I am seeing in class, and what works best for me and my students. However, I am writing for a larger audience, including public school teachers, for whom standardized testing is a reality. Although I have not experienced it myself, I have heard that there exists externally imposed versions of formative assessments. Right now, I’m not going to go into the many drawbacks of this approach, but I will say that in order for formative assessment to be truly transformative, teachers need to be involved. Not only for the reasons I already mentioned, but also because, how can we ever really understand something unless we do it ourselves? For teachers to be able to really understand assessment, they need to be involved in its development. We are always talking about the need for good teachers, but we never give teachers the autonomy they need in order to develop the skills and competencies of excellent educators.

I am not a master of formative assessment. I am still learning everyday, but I am excited by the ways in which it has transformed my teaching practice, and I want to spread the word. I know there are others out there who know more than I do about formative assessment, and whose ideas NEED to be shared. I want to hear from all of you! What has been your experience with assessment? How have your practices changed? What is preventing you from engaging in meaning assessment practices? What are you doing in your classroom that we could all benefit from?

Learning Trajectories for Formative Assessment

One thing I have learned about effective formative assessment is that it is not done on the fly. Sure, I may be in the middle of a lesson one day, and realize that a good number of students have a misconception, or there is some key, prior knowledge that may be missing, and decide that I want to stop and give a quick formative assessment before I move on with instruction. This is what observant, knowledgeable teachers do. However, for formative assessment to have the greatest impact, it needs to be planned BEFORE the unit begins. If I am very clear about what my students are likely to already know (on a spectrum), what the next level of understanding looks like, and which activities will help students reach that next level of understanding, half the battle is won.

Many of us believe that we know these things intuitively, since we have been teaching for so long, and therefore, we don’t need to spend too much time planning. However, let’s take mathematics as an example. If we are being honest with ourselves, how many of us are true mathematicians? I will be the first to admit that I am NOT. I always did pretty well in math throughout my education. I learned the algorithm, than I applied it–no big deal, right? Well, math isn’t taught that way anymore, and besides, being able to DO math, and UNDERSTANDING how mathematical concepts develop are two different things. My school has hired a math tutor for this specific purpose–to help teachers gain a better understanding of how students learn mathematics. Our tutor has been an invaluable resource. Unfortunately, not all schools have access to this type of expertise. So, how can schools empower teachers to become more knowledgeable about mathematics learning?

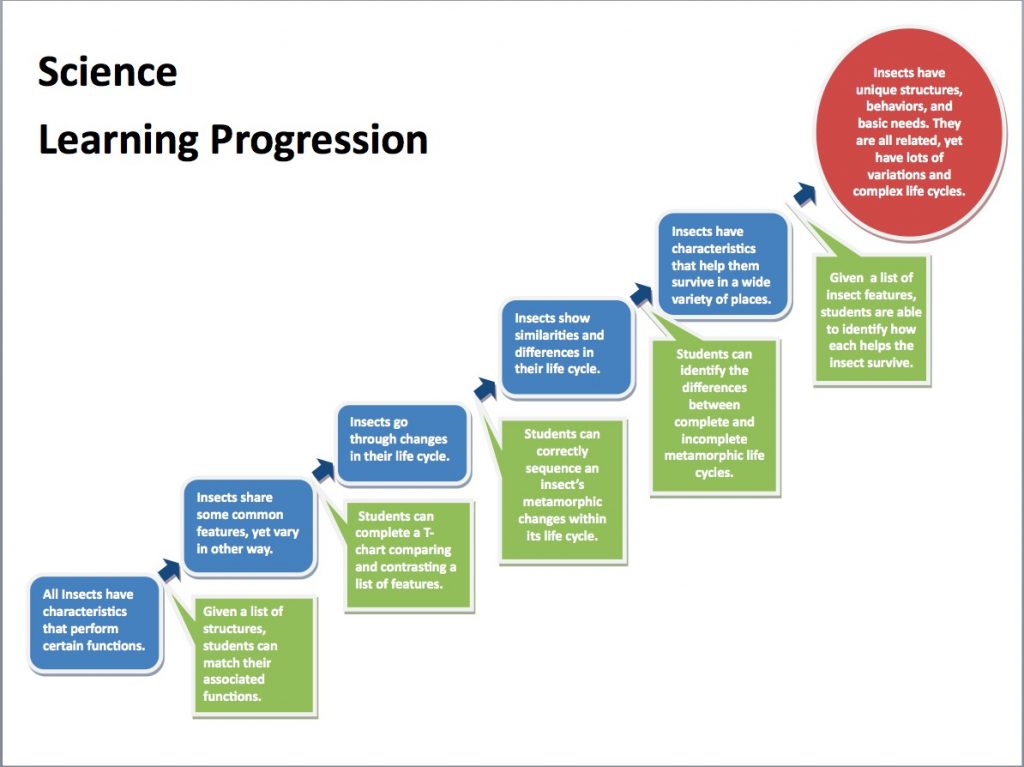

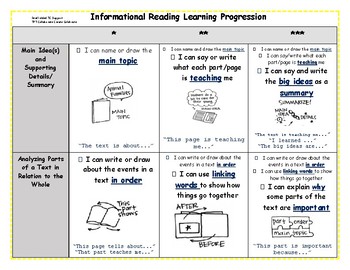

I have done a good deal of research on the topic of learning trajectories, and I am convinced that they are an integral part to the planning of any unit, whether it be math, reading, writing, social studies or science. A learning trajectory has been defined as “a sequence of successively more complex ways of thinking about an idea that might reasonably follow one another in a student’s learning”(Smith et al., 2004, cited in Graf & Ariele-Attali, 2015, p. 196). Basically, I would describe it as a plan for learning which takes into account all possible levels of student understanding.

To develop a learning trajectory you need to start with your standards or scope and sequence documents. First, choose an outcome that is small enough to work with. My example is: “represent and solve problems involving multiplication using efficient mental and written strategies”. Next, you may need to do some research to figure out how student understanding of this outcome grows. Research could include reading, but it could also simply be consulting with a math tutor, or other expert, doing an internet search, or engaging in a brainstorming session with your team members. The goal is to map out, from beginning to end, how students’ understanding develops. Once you have accomplished this, you will want to determine which learning engagements will help students move from one level of understanding to the next. This is going to pay off big time, as your planning will basically be taken care of for the remainder of the unit.

Once you have the trajectory complete, you will need to preassess students, and place them on the trajectory based on what you see. Then, plan for small group instruction. This is the most important part of the entire process. I cannot stress enough how essential differentiation is. You need to find a fun, easy activity that the whole class can engage in without teacher assistance, so you can work with small groups. I usually choose a game that can easily be made more challenging by choosing bigger numbers, or doing an extension. In the meantime, I work with the small groups, including my advanced groups, on developing the skills and understandings they need to move them to the next level. A side note here. It may seem like a lot of time is being wasted as students play a game, while the teacher is working only with a group of 4-5 students. In reality, a lot more time is wasted when you teach the entire class the same concept, and the concept is really only appropriate for, at the most, 30% of the students. I would rather have my class playing a fun and engaging game, which gives them practice, while I work with a small group on exactly the concepts they need and are ready for.

Finally, as the unit progresses, you will need to periodically revisit the trajectory, and make adjustments as needed. This is why learning trajectories are often called ‘hypothetical’. They are, and should be, a work in progress, which is constantly being refined. Your first draft is merely a hypothesis, and your work with students will inform the changes you make.

So, what does this have to do with formative assessment? The real purpose of formative assessment is, or should be, to guide and differentiate instruction. This is precisely what the trajectory accomplishes. It is basically a way of breaking down the curriculum into bite sized chunks so that you have a better understanding of what students need to know, and how you can help them acheive that knowledge. To put it bluntly, formative assessment is ineffective if you, as a teacher, don’t understand what you are teaching.

Now, I know that this all sounds like a lot of work, and it is, but I promise you, it is work that has big returns, and the more you do now, the less you will do later. This school year, I have very little planning to do when it comes to my multiplication unit. I have my trajectory, which includes student understandings, as well as instructional approaches, and I simply need to administer a preassessment and make my groups. Of course, I will continue to tweak the trajectory, and my small groups, but now I can put more of my energy into my students, and less into planning. Also, I recently presented on this topic at the Collaborative for innovative Education (CIE) conference (my school is one of six schools which belong to this collaborative), and a couple of teachers sitting at my table told me that they have created learning trajectories for other mathematics outcomes and they would be happy to exchange (unfortunately, I never heard from them, and I didn’t get their contact info.–call me!). The point is, if we share the work, we will save so much time!

So, this is where I share the work I have done on the multiplication trajectory with you 🙂 If you have done any work on trajectories, please share it with me as well. Also, if you would like to know more about the research on learning trajectories, please read the essay I wrote as part of my Master’s work for the University of Bath, entitled Using Learning Trajectories to Support Formative Assessment in Mathematics: An Example From a Grade Three Unit on Multiplication.

I am curious about what you have to say about learning trajectories. Have you used them? What do you see as the benefits or drawbacks? Do you have any advice for those trying to develop a trajectory?