Video: Feedback Types

Making Feedback Count

Teacher feedback has been on my mind a lot lately. I guess it’s because, with distance learning, feedback has become even more important than before. I only see my students for an hour or two a day, but I see a lot of their work. Feedback has become sort of like a conversation for us, which has been great. I’ll make a comment on an activity, and a student will write back asking for clarification, or explaining what they meant, or giving more information. This has given me the opportunity to reflect on the quality of the feedback I am giving as well as the form it takes. As I examined my feedback I realized that many of my comments do not serve their purpose, which is to have a positive impact on student learning and attitudes. So now I’m asking myself, how are students receiving the feedback I am offering, and how can I make it better, kinder and more impactful?

After a lot of research and reflection, I have come up with three aspects of feedback that I feel are most impactful, and need to be considered:

- The type of feedback we are offering

- The approaches and resources which help students apply feedback

- The manner in which we communicate feedback

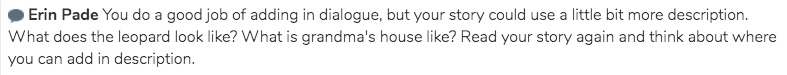

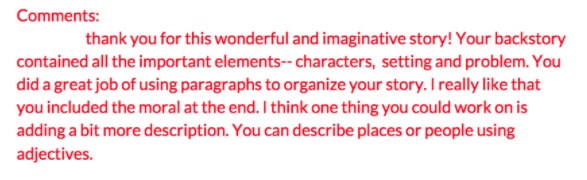

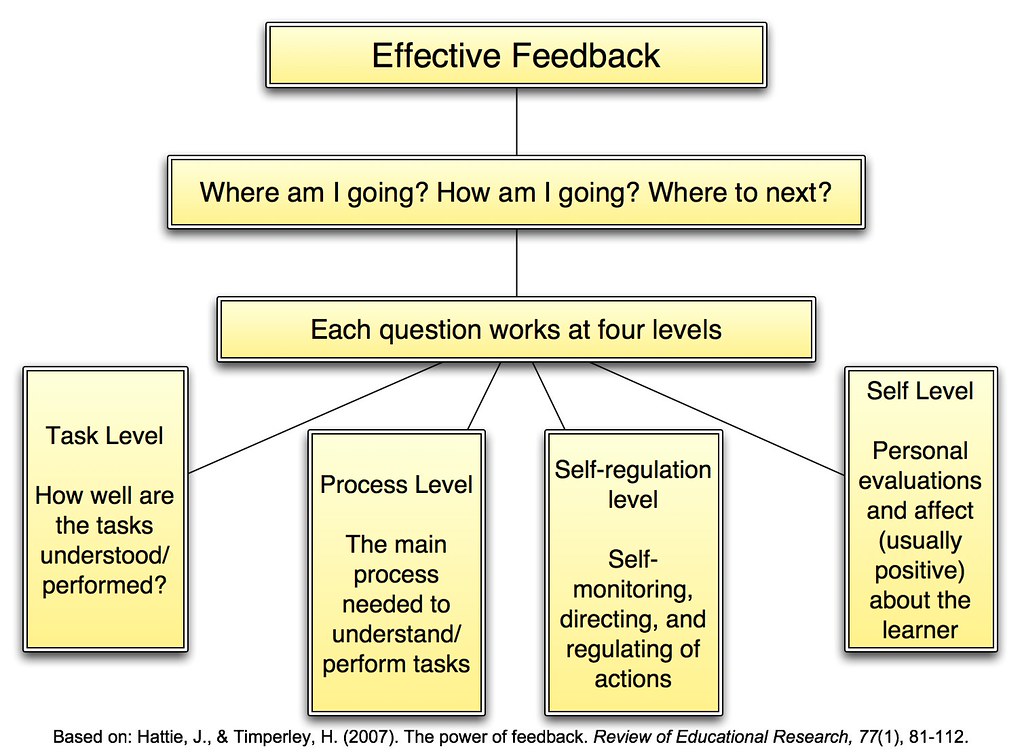

So, the first factor I’ve been considering is the type of feedback I’m giving. A 2007 meta analysis by Hattie and Timperley examined feedback types which led to the development of a feedback model. This model organizes feedback types into four categories: task, process, self-regulation, and self. Self-regulation feedback is connected to self-assessment. These are the reflections that students write about their own learning. For example, “I had a hard time focusing on the activity. Next time I will find a quiet place to work”. These types of comments don’t figure into teacher feedback, and therefore will not be considered here in terms of effectiveness. Task feedback tells whether the work was correct or incorrect, sufficient or deficient. Examples of this type of feedback are “Your story could be a bit longer”, or “You used a lot of interesting vocabulary”. Process feedback focuses on the processes or strategies underlying the task. For example, “Make sure to develop a clear plan before drafting your next story“, or “Watch the video on ‘painting a picture with words’ again. It will show you how you can add adjectives into your piece so it is more descriptive”. Finally, self feedback is non-specific praise such as, “Great job on this!” or “Keep up the good work!”. As you might have guessed, when it comes to teacher feedback, process feedback is most effective if the purpose of the feedback is formative, because it doesn’t just tell students what they can improve, it gives them guidance as to what steps they can take in order to make improvements. Self feedback does little to help students move to the next level of understanding or to improve their product. This seems quite obvious, but if we really take the time to examine the feedback we are giving students we will notice that ‘task’ and ‘self’ comments predominate the content of our comments, especially when we feel like a student has done an exceptional job, and we aren’t sure what other feedback we can offer. Why should we avoid these types of feedback? Is there anything wrong with saying “Great job!”?

Well, there are two very important reasons why we should avoid this type of feedback. The first is that students will model their own comments on those of the teacher. If you have ever engaged your students in peer assessment in the classroom you have seen quite a few ‘self’ feedback comments. “I like your story!” “This was fun to read!” “I think you could do better”. In fact, a study by Harris, Brown & Harnett (2014, accepted) examined self- and peer-assessment feedback comments written by students between the ages of 10 and 15, and found that 79% of comments were ‘task’ or ‘self’ comments, whereas only 16% were process comments and less than 5% were self-regulation comments. Of course, giving good, effective feedback is challenging, especially for students, who cannot be considered content experts, however, teacher modelling certainly plays some role in the prevalence of less effective feedback comments.

Another important reason to avoid ‘task’ and ‘self’ feedback is growth mindset. We want students to focus on learning not achievement. When we give comments such as “This was an excellent piece of work” we are sending the message that what’s important is producing something flawless or excellent, when what we want our students to focus on is growth and next steps. Therefore, the best feedback addresses the growth that the student has made thus far, areas for further growth, and advice on how the student can close the gaps in their understanding. Hattie and Timperley suggest that teachers keep three questions in mind when formulating feedback comments for students: 1) Where am I going? (what is the goal?) 2) How am I going? (what progress is being made toward the goal?), 3) Where to next? (What activities need to be undertaken to make better progress?).

“If we go in with the assumption that every student wants to do their best, and wants to produce high quality work then we have to ask ourselves what conditions and expectations are preventing students from applying feedback”.

Another consideration in terms of feedback is the approaches and resources which help students apply feedback. Just because we give thoughtful feedback on an assignment doesn’t mean a student is going to utilize that feedback. We need to consider why this might be. If we go in with the assumption that every student wants to do their best, and wants to produce high quality work then we have to ask ourselves what conditions and expectations are preventing students from applying feedback. Drafting feedback is a time-consuming endeavor, and we also don’t want to spend valuable time writing comments that will go nowhere.

One reason students may not respond to feedback is that the feedback is too comprehensive and therefore overwhelming to the student. Think about any writing unit as an example. We did a recent unit on writing fairy tales, and the rubric we developed for this unit consisted of four outcomes for structure, two outcomes for development, and four for language conventions. Now, this is helpful for teachers when grading student writing, but If I were to hand a student this rubric they would likely be confused. This is also the case when offering written feedback without a rubric. Too many comments can make the task of revising seem impossible, especially for younger students and struggling writers. The key here is to focus on one thing at a time. Once you’ve seen a couple of samples of a student’s writing, you can determine the aspects which the student needs to work on most. Choose ONE of these aspects. Perhaps a student needs to improve at adding details to their story. Perhaps the student doesn’t have any strategies for fixing up spelling. Maybe they need help with paragraphing. When offering feedback, focus on the one aspect that the student needs the most help with for the time being, and give detailed feedback about that one aspect. Conference with the student, help them identify this as their goal, and give them opportunities to work on that goal all throughout the unit. If at any time you feel they have mastered that one goal, move on to the next one. For some students you may have to focus on one skill for the entire school year. But, isn’t it better to give them the time to focus on that one goal, and have success, than to give them a bunch of different things to focus on and see no results? When a student has a clear, simple goal, they can put all their focus and energy into that goal.

Another reason students may not accept or utilize feedback is that they haven’t developed a growth mindset. Having a growth mindset means that students believe that their abilities can be developed through dedication and hard-work. Students who have a fixed mindset believe that intelligence or ability are innate, and that achievement is more important than growth. These students may view feedback as a criticism of their intelligence or abilities. Accepting feedback means acknowledging their weaknesses, which can be emotionally challenging for some. So, how do we help develop a growth mindset in students when it comes to feedback? One way is to show examples of student work that demonstrate growth. Show an initial draft of a piece of writing, the feedback comments on that draft, and the changes that the student made to improve the piece. Another way is to offer consistent praise to students for applying feedback. Rather than pointing out the things that a student has done well, point out the improvements they have made and celebrate a student’s efforts rather than their accomplishments. Finally, give students the opportunity to give you feedback. Write along with students, show them your work on a regular basis and ask for their opinions. Model a growth mindset by showing appreciation for their feedback, and applying it in your own work.

“In order for self-regulation feedback to be effective, we need to have resources in place that the students can turn to for help”.

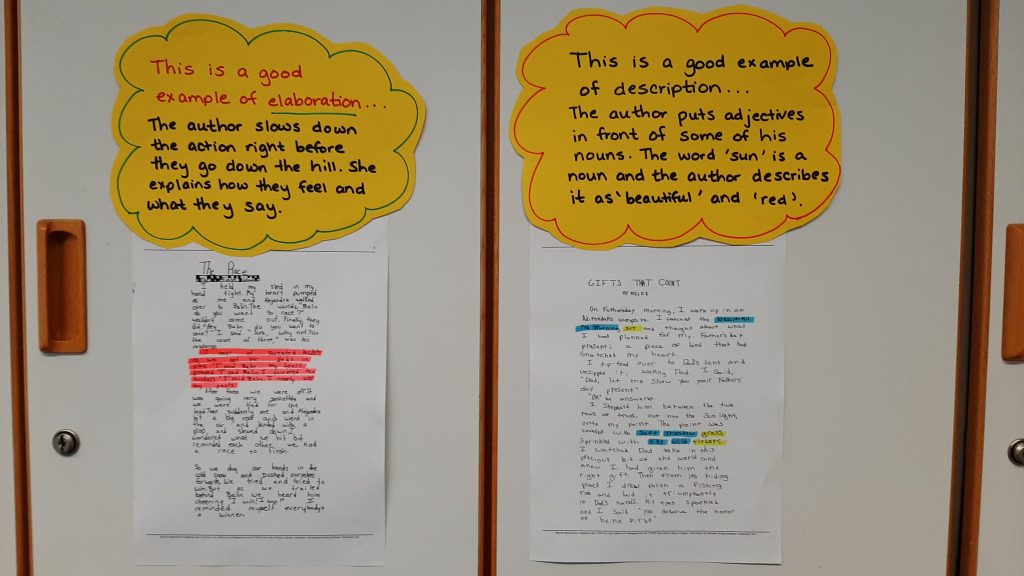

Another important thing to consider is whether there are resources available which will support the student in working toward their goal. While we would like to work with each and every student, this is impossible in a classroom of twenty or more. In middle and high school, students are expected to revise independently (although many of them are not ready for this), however elementary students lack experience. They don’t know where to go to get help. This is why process feedback is so important. We need to tell students not only WHAT they can improve in, but also HOW they can improve in it. But, in order for process feedback to be effective, we need to have resources in place that the students can turn to for help. An example of this is exemplars. Most teachers show students exemplars of ‘good writing’, and point out what makes the writing good. This is so much more powerful than just telling a student what a good piece of writing should have. Why not make these exemplars available to students all the time? You could have a folder containing exemplar pieces which relate directly to each outcome, or they could be posted on the wall.

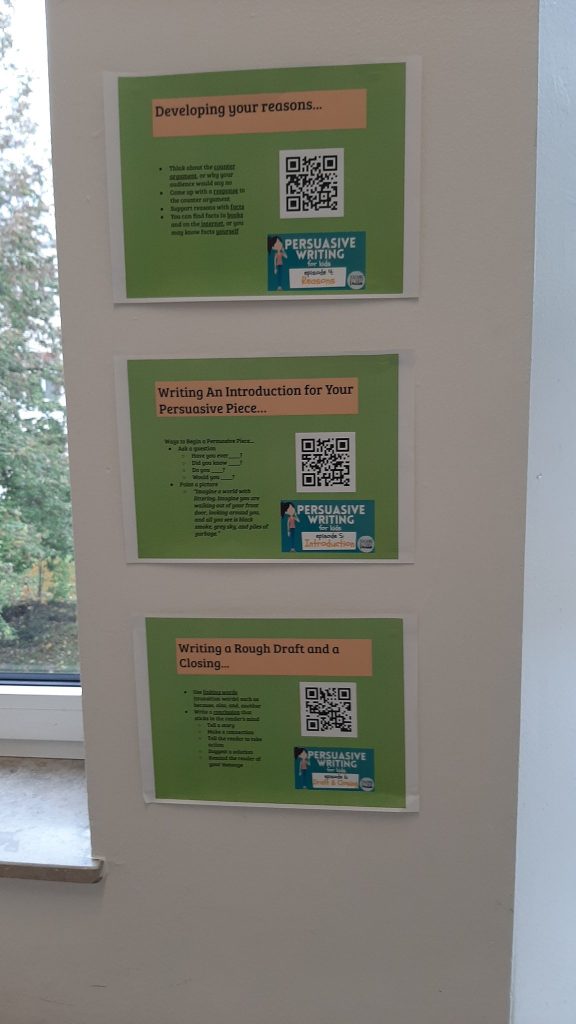

You could even record yourself reading an excerpt from an exemplar and pointing out the skill that you want students to focus on in that piece and have these recordings available to students. In my opinion, it is better to have multiple examples of good student writing, which each highlight one outcome than to show a ‘good’ piece of writing and point out all the things the writer is doing well. I can imagine how overwhelming this might feel for a student, who suddenly is supposed to notice several skills which they might not possess themselves. Another possibility is to make instructional videos available to students. I got a great idea from a colleague of mine who created posters with QR codes which linked to instructional videos. Post these in the classroom where the students can access them independently. If a student needs help with writing a powerful introduction, for example, you can direct them to the instructional video about this skill.

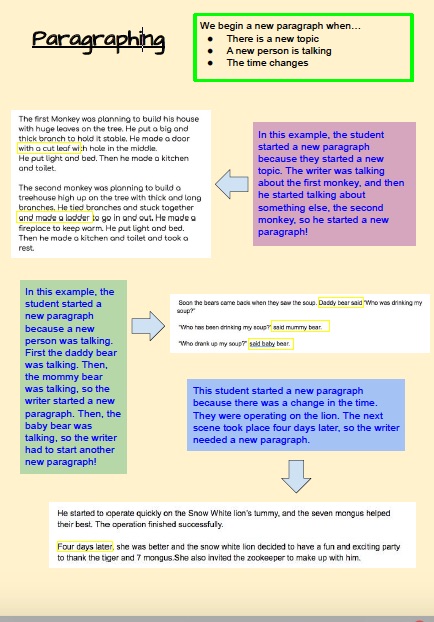

We also had a visitor from The Columbia Readers and Writers Project who showed us a really good idea. She had created a folder organized by subtopic which had a page dedicated to each outcome. Each page had examples, explanations and images for the outcome. She had created this folder as a teaching tool which she could use during small group instruction, but it could also be a resource that students could refer to independently. While this is a time-consuming undertaking, it is one of those things which, when it is done, becomes an invaluable resource. It is also something you can add to as the year goes on, and then you can have a finished product at the end of the school year which you can continue to utilize in the coming years. A team of teachers could take one or two pages each and make copies of these so every team member could have a folder of their own. Of course, it is important that you model for students how to use these resources so that they can be successful. Students need to be sure about where they can go for help and how to use the resources. They are already facing some challenging work with trying to learn a new skill; we don’t want to add the extra challenge of trying to access a resource that is not clear and user-friendly.

Finally, we need to consider The manner in which we communicate feedback. Naturally, feedback needs to be comprehensible to a student, and a comment may not be understood for several reasons. Perhaps that student is a beginning reader, or a language learner, or maybe the vocabulary is too challenging. When we offer feedback to a student we need to keep the student in mind. There’s no point in writing comments that we’re just going to have to explain later. If feedback is written, it needs to, of course, be in simple, kid-friendly language. But, what if that student is a struggling reader or an EAL student? In that case, even clear, simple feedback may be incomprehensible. Just the fact that the student doesn’t understand the feedback in the first place may produce a lot of anxiety and self-doubt. Are there other, better ways of offering feedback so that it is clear the first time?

Well, I have always loved conferencing with students. This is a routine that is built into the readers’ and writers’ workshop. It is helpful to sit down with a student one-on-one to talk about their work and offer feedback. The advantage here is that there are a lot of body and facial cues which help you determine whether a student is understanding what you are saying or not. When you feel like the student is not understanding, you can say it a different way. The student can ask questions. You can refer directly to specific places in the text. You can point the student in the direction of resources that they can use to help them revise their work. But, let’s be honest; realistically, we can only see three, at the most four, students per class period. Feedback needs to be timely. What is the rest of the class doing while you’re working with those three to four students? Another drawback to oral feedback which you don’t have with written feedback is that, unless you record what you are saying, the message gets lost. Therefore, the next time the student is working they don’t have that feedback next to them to refer back to. So, how can we combine the best of both worlds?

There is recent research on the use of audio and video feedback as an alternative to traditional methods. Granted, these studies involve older students, however, the data is pretty clear that this type of feedback is preferred by students. They say it is easier to understand, has more depth and is more personal than written feedback (Crook et al., 2012). Also, video and audio feedback have been shown to be most effective in helping students make meaningful revisions to their work (Hattie, 1999). Teachers find video and audio feedback better because they can adjust the volume and pitch of their voice to highlight specific points which aids comprehension. The added benefit of video feedback is that students can gauge the reactions of the teacher through body language and facial expressions; this aspect also makes the feedback easier to understand. Additionally, audio and video feedback are recorded, so they can be accessed again by students.

So video feedback is an option that maybe you want to try out. It is more personal, more emotive and more effective. The only thing that’s missing is the interaction that we gain through conferencing. Perhaps a mixture of conferencing and video feedback would be the answer. The other option is to video your conferences with students and share those with them.

Distance learning has been an opportunity to try out new strategies for offering effective feedback. As we move back into the classroom we should consider which aspects of this we can and should retain. I’m curious to hear which feedback strategies you’ve tried out in recent months. Is there anything that has worked really well? Which new strategies would you like to try out? Do you have any additional examples of effective feedback strategies? Please, share your ideas in the comments!!